| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:西伯利亚森林猫 |

| 年龄:5岁 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:未知 | |

| 诊断:肾脏组织细胞肉瘤 | |

01 主诉及病史

因嗜睡、食欲不振和体重减轻一周就诊,接受两天的阿莫西林/克拉维酸治疗效果不佳。既往病史无异常。

02 检查

该猫安静、机警、反应灵敏,粘膜苍白/粉红,患有中度牙病和腭咽炎。心率为200次/分,呼吸36次/分,直肠温度正常(39.2°C)。腹部触诊时紧张,但无法确定是由于疼痛还是害怕。该猫身体状况很差(2/9 分),全身肌肉严重萎缩。据主人报告,该猫可能存在长期的体重下降。

全血细胞计数、血清生化和尿液分析结果表明存在多项异常。WBC 44.2×10^9/L(4-15),RBC 4.47×10^12/L(5.5-10),血红蛋白6.9 g/dL(8-15),PCV 24%(27-50),中性粒细胞36.7×10^9/L(2.5-12.5),单核细胞0.9×10^9/L(0-0.8),嗜酸性粒细胞1.8×10^9/L(0-1.5),ALP 5 U/L(11-67),CK 608 U/L(0-360),葡萄糖8 mmol/L(3.8-7.6),VB12 542 pmol/L(220-500),叶酸13.6 nmol/L(19-37),尿蛋白0.85(<0.4),猫逆转录病毒筛查呈阴性。

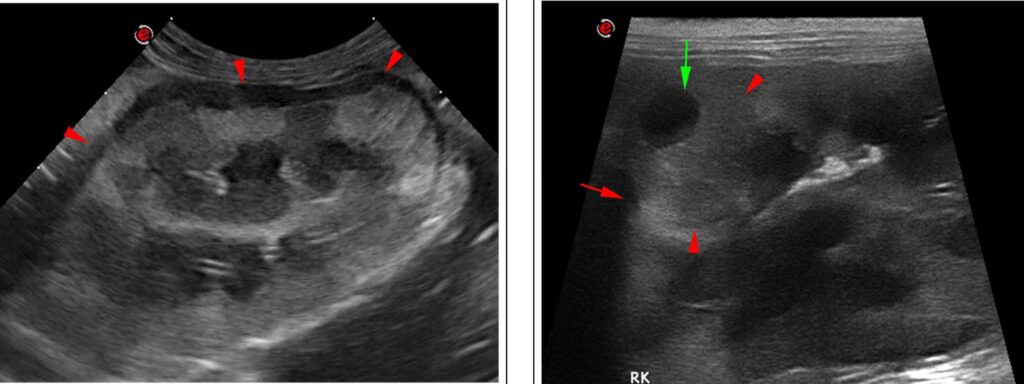

腹部超声波检查显示双侧肾脏增大(长4.5 cm),形状不规则扭曲。两个肾脏的皮质回声不均匀,囊下有低回声边缘(下图左),至少有三个皮质隆起的结节,大小为1-5 mm,并伴有低回声区(左肾一个,右肾两个)(下图右)。未发现肾积水,但有少量腹膜后渗出。这些特征与双侧肾肿瘤一致,淋巴瘤可能性大。超声引导下对肾皮质和囊下缘进行细针抽吸以进行细胞学检查。

细胞学显示有大量不典型细胞,分化很差。这些细胞呈多角形,含有中等量到大量苍白的嗜碱性细胞质。核与细胞质的比例适中,核偏心,染色质呈网状,可见大核仁。一些细胞出现嗜红细胞和嗜白细胞现象,偶尔看到有丝分裂。考虑为组织细胞肉瘤。

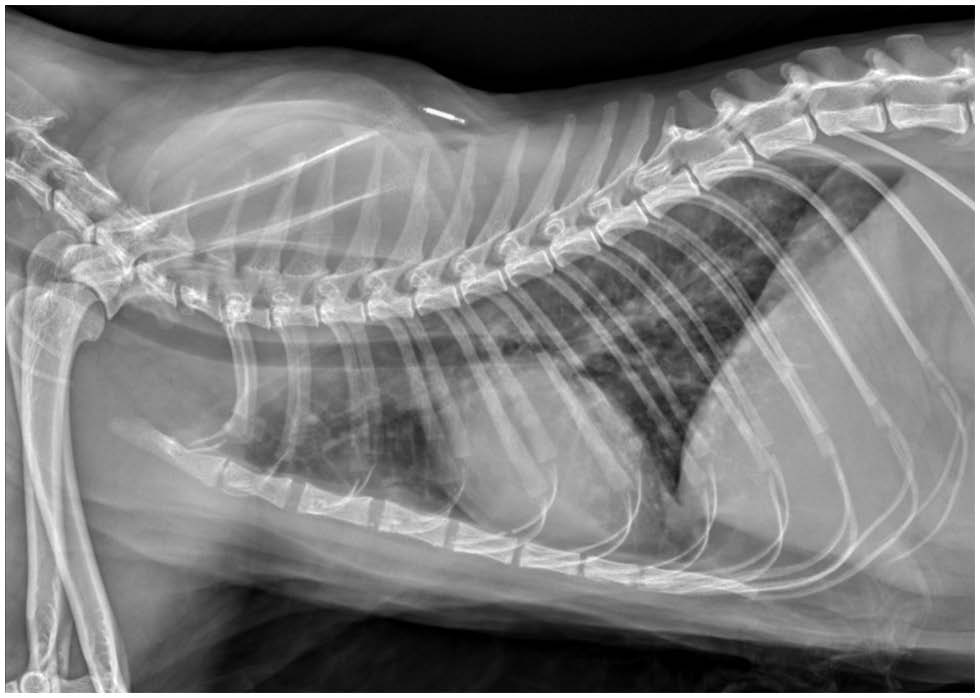

胸片显示,肺叶周围存在中等数量的软组织结节,呈圆形到略微不规则,直径可达4 mm(下图)。

03 预后

鉴于高度怀疑该猫患有恶性转移性肿瘤,且长期预后不佳,主人决定对其实施安乐死。

04 尸检

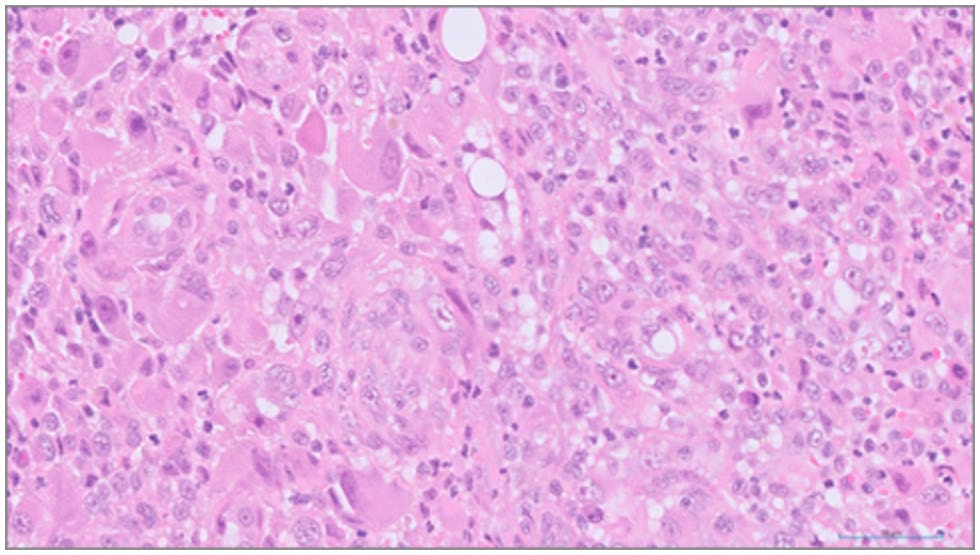

组织病理学评估证实,肾脏及肺部的肿瘤细胞外观非常相似。在右肾样本中,肿瘤细胞浸润在原有的肾小管之间,有些地方完全侵蚀了正常的组织结构。肿瘤细胞还伴有数量不等的中性粒细胞、反应性成纤维细胞和可能坏死的出血区域(下图)。肿瘤细胞存在异核和异细胞,每个高倍视野可见0-2个有丝分裂像。其外观和生长模式最有可能是组织细胞肉瘤。

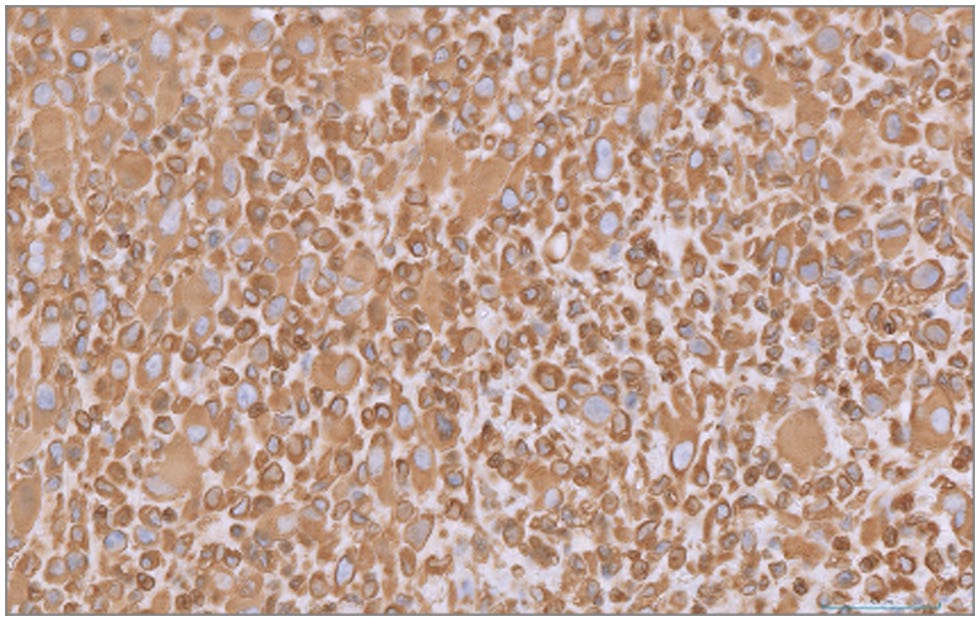

免疫组化染色显示肿瘤细胞群的间质细胞标志物波形蛋白细胞质染色呈强阳性(下图),而上皮细胞标志物细胞角蛋白呈阴性,与肉瘤一致。

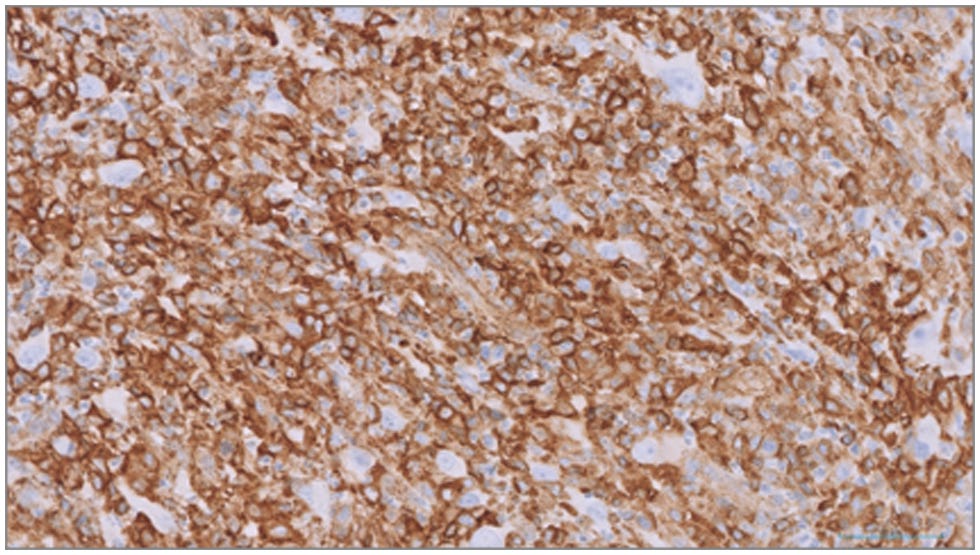

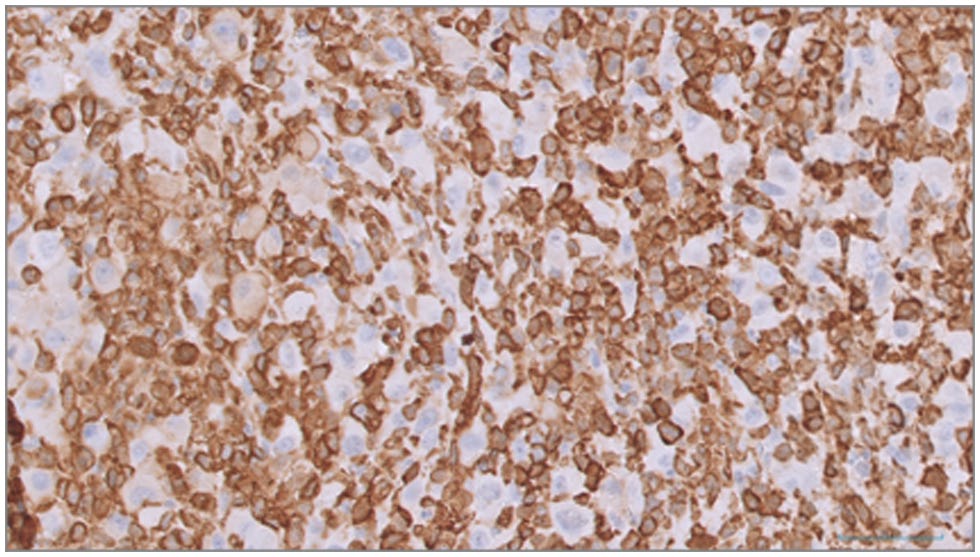

大部分肿瘤细胞的组织细胞标记物MHC II类(下图上)和Iba-1(下图下)呈阳性染色,但较大细胞的一个亚群似乎对这些标记物呈阴性染色。

05 讨论

在狗身上已经发现了几种组织细胞增生性疾病,但在猫身上描述得较少[1,2],通常仅限于猫进行性组织细胞增生症、组织细胞肉瘤(histiocytic sarcoma,HS)和肺朗格汉斯细胞组织细胞增生症(PLCH)[1]。

鉴于组织细胞疾病的起源——巨噬细胞或树突状细胞的分布无处不在,HS几乎可产生于任何组织[1,3]。迄今为止,猫科动物HS的病变部位包括中枢神经系统[4-7]、眼睛[8]、口腔和鼻腔[9-11]、纵隔[12-14]和关节周围[15,16]。当HS出现在一个以上器官时,原发部位往往难以确定。以前曾描述过骨[11]、心脏[16]和肾脏[6]转移。多中心疾病和原发肿瘤伴远处转移病灶均被称为播散性HS[1,17],以前也称为恶性组织细胞增生症(MH)[18-21]。

关于HS影响猫肾脏的报道非常有限。在两篇已发表的病例报告中,肾脏受累被认为是其他部位原发性肿瘤播散导致的[6,21]。在本病例报告之前,还没有关于猫双侧原发性肾HS的病例报道。

除MH[21] 外,文献中也未明确描述原发性HS导致继发的肺部转移。其他形式的组织细胞病,如PLCH主要累及肺部[22],并经常累及其他器官,包括淋巴结、脾脏、肝脏、肾脏、甲状腺和甲状旁腺[1,2,23]。虽然本病例中出现的肺结节也可能与PLCH有关[2],但由于没有呼吸功能不全(PLCH的主要临床表现)的记录[2,23],因此在本病例中的猫似乎不太可能是PLCH。

其他研究曾描述过HS在狗[24]和猫[25]中的超声表现。在这些研究中,在大多数患病动物的肝脏和脾脏中观察到低回声不规则结节,回声混杂,中心以低回声为主,与本病例肾皮质中发现的双侧结节相似。在本病例中,其他发现与常见的肾淋巴瘤相似(如弥漫性回声改变、双侧肾脏肿大、肾脏轮廓变形和囊下低回声增厚)[26],而肾淋巴瘤是猫科动物最常见的肾脏肿瘤[17,27]。因此,当根据超声特征怀疑肾淋巴瘤时,尤其是在肾皮质内也发现低回声结节时,应将HS作为鉴别诊断。

HS明确诊断需要组织细胞的形态学和免疫组化证实[6]。在该病例中,肿瘤细胞的免疫组化染色模式与肉瘤一致,波形蛋白呈阳性染色。大部分肿瘤细胞Iba-1(巨噬细胞/单核细胞系)和MHC II(抗原递呈细胞)也呈阳性染色,支持组织细胞起源[8,14,28]。然而,一小部分较大的肿瘤细胞显示阴性染色,因此不能完全排除其他形式肉瘤的可能性,特别是未分化多形性肉瘤[29]。

当HS出现在一个以上的器官时,往往很难确定原发部位。在本病例中,既没有进行全身影像诊断,也没有进行尸检,因此无法明确排除其他器官存在组织细胞病。尽管如此,根据现有信息,考虑到明显的超声变化以及组织病理学和免疫组化结果,作者强烈怀疑HS源自肾脏。肺部结节被怀疑是肿瘤播散所致。

HS猫的预后很差,有关治疗方案和反应的数据也很有限[14,30,31],而犬HS治疗的信息较多[30,31]。人类HS的预后也很差,大多数患者会在确诊后1年内死亡[32]。对猫科动物HS认识的提高有望提供更多治疗方案和预后信息。

参考文献

[1] Moore PF. A review of histiocytic diseases of dogs and cats. Vet Pathol 2014; 51: 167–184.

[2] Argenta FF, de Britto FC, Pereira PR, et al. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in cats and a literature review of feline histiocytic diseases. J Feline Med Surg 2020; 22: 305–312.

[3] Hirabayashi M, Chambers JK, Sumi A, et al. Immunophenotyping of nonneoplastic and neoplastic histiocytes in cats and characterization of a novel cell line derived from feline progressive histiocytosis. Vet Pathol 2020; 57: 758–773.

[4] Vernau KM, Higgins RJ, Bollen AW, et al. Primary canine and feline nervous system tumors: intraoperative diagnosis using the smear technique. Vet Pathol 2001; 38: 47–57.

[5] Ide T, Uchida K, Tamura S, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma in the brain of a cat. J Vet Med Sci 2010; 72: 99–102.

[6] Monteiro S, Hughes K, Genain MA, et al. Primary histiocytic sarcoma in the brain with renal metastasis causing internal ophthalmoparesis and external ophthalmoplegia in a Maine Coon cat. JFMS Open Rep 2021; 7.

[7] Riker J, Clarke LL, Demeter EA, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma with central nervous system involvement in 6 cats. J Vet Diagn Invest 2023; 35: 87–91.

[8] Scurrell E, Trott A, Rozmanec M, et al. Ocular histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. Vet Ophthalmol 2013; 16 Suppl 1: 173–176.

[9] Santifort KM, Jurgens B, Grinwis GC, et al. Invasive nasal histiocytic sarcoma as a cause of temporal lobe epilepsy in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2018; 4.

[10] NéčováS, North S, Cahalan S, et al. Oral histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2020; 6.

[11] Ruppert SL, Ferguson SH, Struthers JD, et al. Oral histiocytic sarcoma in a cat with mandibular invasion and regional lymph node metastasis. JFMS Open Rep 2021; 7.

[12] Walton RM, Brown DE, Burkhard MJ, et al. Malignant histiocytosis in a domestic cat: cytomorphologic and immunohistochemical features. Vet Clin Pathol 1997; 26: 56–60.

[13] Smoliga J, Schatzberg S, Peters J, et al. Myelopathy caused by a histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 2005; 46: 34–38.

[14] Bisson J, Van den Steen N, Hawkins I, et al. Mediastinal histiocytic sarcoma with abdominal metastasis in a Somali cat. Vet Rec Case Rep 2017; 5.

[15] Pinard J, Wagg CR, Girard C, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma in the tarsus of a cat. Vet Pathol 2006; 43: 1014–1017.

[16] Chalfon C, Romito G, Sabattini S, et al. Periarticular histiocytic sarcoma with heart metastasis in a cat. Vet Clin Pathol 2021; 50: 579–583.

[17] Williams AG, Hohenhaus AE, Lamb KE. Incidence and treatment of feline renal lymphoma: 27 cases. J Feline Med Surg 2021; 23: 936–944.

[18] Moore PF, Rosin A. Malignant histiocytosis of Bernese mountain dogs. Vet Pathol 1986; 23: 1–10.

[19] Freeman L, Stevens J, Loughman C, et al. Clinical vignette. J Vet Intern Med 1995; 9: 171–173.

[20] Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee on Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997; 29: 157–166.

[21] Kraje AC, Patton CS, Edwards DF. Malignant histiocytosis in 3 cats. J Vet Intern Med 2001; 15: 252–256.

[22] Vail DM, Thamm DH, Liptak JM. (eds). Withrow and MacEwen’s small animal clinical oncology. Vol. I. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2019.

[23] Busch MDM, Reilly CM, Luff JA, et al. Feline pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis with multiorgan involvement. Vet Pathol 2008; 45: 816–824.

[24] Huber B, Leleonnec M. Diagnosis and treatment of hemophagocytic histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2020; 6.

[25] Cruz-Arámbulo R, Wrigley R, Powers B. Sonographic features of histiocytic neoplasms in the canine abdomen. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2004; 45: 554–558.

[26] Valdés-Martínez A, Cianciolo R, Mai W. Association between renal hypoechoic subcapsular thickening and lymphosarcoma in cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2007; 48: 357–360.

[27] Mooney SC, Hayes AA, Matus RE, et al. Renal lymphoma in cats: 28 cases (1977-1984). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 191: 1473–1477.

[28] Teshima T, Hata T, Nezu Y, et al. Amputation for histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 147–150.

[29] de Cecco BS, Argenta FF, Bianchi RM, et al. Feline giant-cell pleomorphic sarcoma: cytologic, histologic and immunohistochemical characterization. J Feline Med Surg 2021; 23: 738–744.

[30] Rassnick KM, Moore AS, Russell DS, et al. Phase II, open-label trial of single-agent CCNU in dogs with previously untreated histiocytic sarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2010; 24: 1528–1531.

[31] Cannon C, Borgatti A, Henson M, et al. Evaluation of a combination chemotherapy protocol including lomustine and doxorubicin in canine histiocytic sarcoma. J Small Anim Pract 2015; 56: 425–429.

[32] Tocut M, Vaknine H, Potachenko P, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma. Isr Med Assoc J 2020; 22: 645–647.