| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:中毛猫 |

| 年龄:10岁 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:是 | |

| 诊断:不全性骨折 | |

01 主诉及病史

右后肢跛行2个月。

该猫在1岁时曾因持续不明原因高钙血症而被诊断为特发性高钙血症(IHC),医生给它开了泼尼松龙和阿仑膦酸钠来控制病情,并根据血钙水平逐渐调整用药剂量。最后一次有记录的IHC发生在确诊后的3年。目前的药物包括阿仑膦酸钠(10 mg/周)、泼尼松龙(2.5 mg/日)和加巴喷丁(100 mg/8小时)。

02 检查

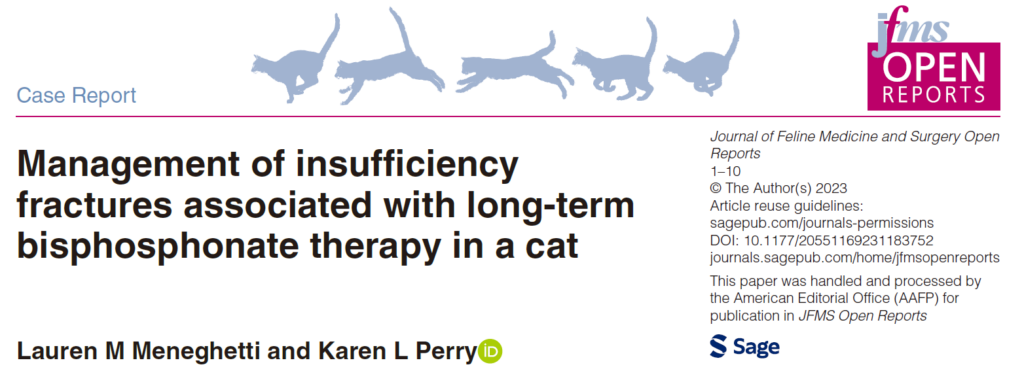

右后肢中度负重跛行,跗关节中度过度屈曲。右跗关节活动范围正常,可触及轻微捻发音。X光检查发现右侧小腿骨完全横向骨折,骨折端有轻度移位和中度硬化,骨折部位活动度极小(下图)。虽然建议进行手术治疗,但由于随着时间的推移情况有所好转,主人选择了非手术治疗。

6周后,该猫因左后肢急性非负重性跛行再次就诊。检查证实该猫左后肢无负重跛行,右后肢轻度负重跛行,并伴有持续性跗骨外翻。X光片显示,左侧胫骨近端骨骺和腓骨完全横向骨折(下图a)。右侧小腿骨的骨折仍处于静止状态,骨折线持续存在,骨质硬化,活动度极小(下图b)。除总钙含量略低(8.2 mg/dL,区间:9.1-10.7)外无明显异常,钙(5.5 mg/dL,区间:5.1-6.0)和磷(5.3 mg/dL,区间:2.7-5.7)均在正常范围内。

03 手术

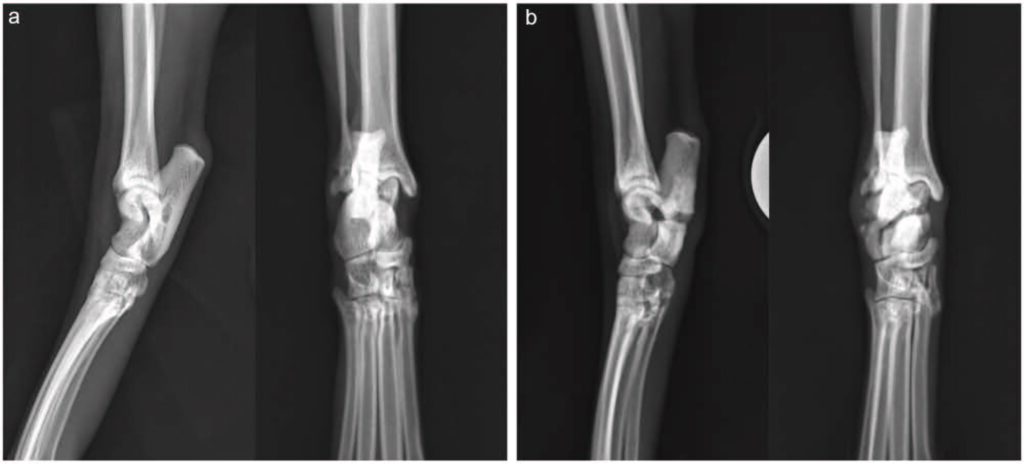

通过内侧入路进行了左侧胫骨切开复位和内固定术。放置了一块 1.5 mm的六孔加压钢板用于纠正骨折。内侧放置了一块1.5/2.0 mm的T型七孔加压钢板。术后X光片显示解剖对位、植入位置适当(下图)。虽然考虑过进行骨活检,但由于骨质较脆,可用于修复的骨量较少,因此没有进行。

04 预后

术后住院期间使用美沙酮(0.2 mg/kg IV,q6h)镇痛。第二天出院,使用金刚烷胺(2.9 mg/kg PO q24h)以增加镇痛效果,并继续服用目前的药物(泼尼松龙 2.5 mg q24h,加巴喷丁 100 mg q8h),但停用阿仑膦酸钠。 在术后17个月随访时,对骨盆、左侧胫骨、右侧胫骨(下图)和双侧跗骨进行了X光检查,未发现骨折的迹象。

05 讨论

双膦酸盐(Bisphosphonate,BP)在人类医学中的应用非常广泛,它在治疗骨质疏松症、恶性肿瘤高钙血症、骨转移和成骨不全等方面的研究很多[1-3]。在兽医领域,BP在治疗甲状旁腺功能亢进、特发性高钙血症(Idiopathic hypercalcemia,IHC)、继发性高钙血症、牙齿吸收和肿瘤性骨痛等方面越来越受到青睐[3-10]。

BP是强效的破骨细胞抑制剂,可减少破骨细胞诱导的骨吸收和重塑[1,11]。最广泛使用的BP含氮,包括阿仑膦酸盐、利塞膦酸盐和唑来膦酸盐。这些化合物与骨结合,经内吞进入破骨细胞,并通过抑制多种酶(主要是法尼酰二磷酸合酶)阻碍代谢途径[12]。这种代谢途径能够破坏破骨细胞参与骨吸收的活动[12]。破骨细胞凋亡也可能发生,但并非为抑制骨吸收的必要条件[13,14]。

在人类文献报道的使用BP所产生的不良反应中,非典型应力性骨折或不全性骨折最受关注[15-26]。不全性骨折发生在没有外伤的情况下,当生理应力作用在异常骨骼上时[27,28],而应力性骨折则是指当重复力作用在正常骨骼上时造成的损伤[29,30]。

人类使用BP可能引起的其他并发症包括颌骨骨坏死[31-34]、肌肉骨骼疼痛[35]、心房颤动[36-38]和食道刺激[2]。在兽医领域,大多数BP的使用都是短暂的,因此尚未发现常见的副作用。然而,长期使用BP治疗与一只猫的双侧非典型髌骨骨折和颌骨骨坏死有关[9,39]。

本病例报告描述了一只服用阿仑膦酸钠控制IHC的猫在没有外伤的情况下发生非典型骨折。这是仅有的第二例BP相关性猫骨折病例,也是第一例通过手术治疗骨折并进行长期随访的病例。

在长期服用BP的人类患者身上,可通过X光诊断出即将发生的骨折,进而发展为完全性骨折。这些应力反应通常是皮质内硬化或局灶性不透明增加的区域,但也可能只有皮质的轻微隆起[18,22]。有报告称,一只疑似小腿骨应力性骨折的猫也出现了类似的变化[42]。

本病例报告中详细描述的这只猫在左侧胫骨骨折前6周接受了左侧胫骨的X光检查,作为右侧骨折常规检查的一部分。但当时没有发现与左后肢有关的异常。回过头看,在6周前的左胫骨近端骨皮质处发现了应力反应,这与随后的胫骨骨折部位相符(下图)。

由于识别此类放射学特征有助于预测即将发生的骨折,因此可能需要对长期服用BP的猫进行连续的放射学监测。由于微损伤的积累导致骨折需要数年时间,而微裂缝密度与BP治疗持续时间呈线性关系,因此此类监测的时限仍不确定[43]。

由于两只患有BP相关骨折的猫都是在服药8年后才出现骨折,而人类往往在服药3-9年后才出现骨折[17,21,26],因此可能不需要立即开始监测。在开始BP治疗时获得基线X线照相结果并考虑在5年后每年进行X线检查可能是一个合理的建议。如果出现疼痛或跛行等临床症状,则应更早开始监测。

目前尚不清楚猫体内BP在骨骼中的半衰期,但由于人(10年)[44]和狗(3年)[45]的半衰期较长,因此在停止治疗后的数年内仍需继续监测。在本报告详述的这只猫中,术后17个月进行的放射线监测显示没有骨折反应的迹象。

与在人类中的使用相比,在动物中使用BP的研究并不多,但有病例报告和回顾性研究描述了BP的使用和相关并发症[3-6,10,46-50]。在狗的治疗中,BP通常用于短期治疗,如用于引起高钙血症的中毒和骨肿瘤的姑息治疗,目前还没有BP相关骨折的报告[3,4,48,49]。

狗曾被用于评估BP对人类副作用的研究,但这些研究的治疗期相对较短[51-53]。这就降低了出现骨折的可能性,因为在其他物种中,不完全性骨折往往是在多年治疗后才出现的[17,21,26]。

在兽医学中,猫科动物IHC是长期使用BP的最常见适应症[4-6,10]。虽然对猫科动物IHC长期治疗病例的长期随访很少,因此不良反应的发生率尚不清楚。除了以前的报告[7]外,本报告还指出,应提醒饲养者注意不完全性骨折形成的风险。

长期的糖皮质激素治疗会减少骨转换,已被确定为不完全性骨折形成的一个危险因素[20]。长期服用类固醇会抑制家兔骨折的愈合[54],而且已知类固醇会降低成骨细胞的活性,从而减少基质的合成[55-58]。应该考虑的是,长期泼尼松龙治疗可能会夸大阿仑膦酸钠在这只猫身上的作用,无论是在骨折易感性方面还是在延迟愈合方面都是如此。

在已发表的唯一一例与BP相关的猫骨折病例报告中,一只缅因猫因长期接受阿仑膦酸钠治疗以防止牙齿吸收进展,导致双侧髌骨骨折[7]。该猫的长骨皮质明显比对照组的厚[7]。根据之前描述的测量结果[7],本报告中详细描述的这只猫的胫骨髓腔直径是通过每组射线照片计算得出的,但没有证据表明髓腔变窄或皮质变厚。

在人类[17,20,21]和本病例中都可以观察到接受BP治疗的患者不全性骨折延迟愈合的情况。在这只猫中,胫骨骨折修复后停止了阿仑膦酸钠治疗,以降低发生其他骨折的风险,并促进目前骨折的愈合。然而,根据之前对人类进行的一项研究表明,可能是由于阿仑膦酸钠的半衰期较长,停止阿仑膦酸钠治疗的患者与继续使用阿仑膦酸钠治疗的患者在骨折愈合方面没有差异[20]。

由于BP相关骨折的猫数量极少,因此无法就是否应该停用BP以降低未来骨折风险提出明确建议。不过,鉴于BP的半衰期较长,正如在狗和人身上的报道一样[44,45],停用BP不太可能对已经发生的骨折愈合产生重大影响。

由于预计骨折愈合时间较长,因此应相应地制定计划。考虑到猫胫骨骨折稳定后钢板弯曲的风险[63],使用正交钢板固定[64]或使用角度稳定的交锁钉[65]的风险较低,因此在BP相关胫骨骨折病例中应考虑后两种方法。本病例中的正交钢板植入术效果非常理想,在术后17个月未出现与植入物相关的并发症。

参考文献

[1] Rodan GA. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1998; 38: 375–388.

[2] Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83: 1032–1045.

[3] Suva LJ, Cooper A, Watts AE, et al. Bisphosphonates in veterinary medicine: the new horizon for use. Bone 2021; 142.

[4] Hostutler RA, Chew DJ, Jaeger JQ, et al. Uses and effectiveness of pamidronate disodium for treatment of dogs and cats with hypercalcemia. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19: 29–33.

[5] Whitney JL, Barrs VR, Wilkinson MR, et al. Use of bisphosphonates to treat severe idiopathic hypercalcaemia in a young Ragdoll cat. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 129–134.

[6] Hardy BT, de Brito Galvao JF, Green TA, et al. Treatment of ionized hypercalcemia in 12 cats (2006–2008) using PO-administered alendronate. J Vet Intern Med 2015; 29: 200–206.

[7] Council N, Dyce J, Drost WT, et al. Bilateral patellar fractures and increased cortical bone thickness associated with long-term oral alendronate treatment in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2017; 3.

[8] Salwat SM, Farid MHM, Hakam HM. Potential effect of alendronate on tooth eruption and molar root formation in young growing and osteoprotic albino rats (A histiological and histochemical study). Al-Azhar Dent J Girls 2018; 5: 237–242.

[9] Larson MJ, Oakes AB, Epperson E, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after long-term bisphosphonate treatment in a cat. J Vet Intern Med 2019; 33: 862–867.

[10] Kurtz M, Desquilbet L, Maire J, et al. Alendronate treatment in cats with persistent ionized hypercalcemia: a retrospective cohort study of 20 cases. J Vet Intern Med 2022; 36: 1921–1930.

[11] Russell RG, Muhlbauer RC, Bisaz S, et al. The influence of pyrophosphate, condensed phosphates, phosphonates and other phosphate compounds on the dissolution of hydroxyapatite in vitro and on bone resorption induced by parathyroid hormone in tissue culture and in thyroparathyroidectomised rats. Calcif Tissue Res 1970; 6: 183–196.

[12] Rogers MJ, Monkkonen J, Munoz MA. Molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates and new insights into their effects outside the skeleton. Bone 2020; 139.

[13] Roelof AJ, Ebetino FH, Reszka AA, et al. Bisphoshonates. Mechanism of action. In: Bilezikian J, Raisz L, Martin TJ. (eds). Principles of bone biology. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2008, pp 1737–1767.

[14] Baron R, Ferrari S, Russell RG. Denosumab and bisphosphonates: different mechanisms of action and effects. Bone 2011; 48: 677–692.

[15] Whyte MP, Wenkert D, Clements KL, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced osteopetrosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 457–463.

[16] Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, et al. Aspects of in vitro fatigue in human cortical bone: time and cycle dependent crack growth. Biomaterials 2005; 26: 2183–2195.

[17] Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, et al. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 1294–1301.

[18] Kwek EBK, Goh SK, Koh JSB, et al. An emerging pattern of subtrochanteric stress fractures: a long term complication of alendronate therapy?. Injury 2008; 39: 224–231.

[19] Geusens P. Bisphosphonates for postmenopausal osteoporosis: determining duration of treatment. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2009; 7: 12–17.

[20] Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy. A systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone 2010; 47: 169–180.

[21] Sellmeyer DE. Atypical fractures as a potential complication of long-term bisphosponate therapy. JAMA 2010; 304: 1480–1484.

[22] Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 1555–1565.

[23] Giusti A, Hamdy NAT, Dekkers OM, et al. Atypical fractures and bisphosphonate therapy: a cohort study of patients with femoral fracture with radiographic adjudication of fracture site and features. Bone 2011; 48: 966–971.

[24] Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1728–1737.

[25] Dell RM, Adams AL, Greene DF, et al. Incidence of atypical nontraumatic diaphyseal fractures of the femur. J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27: 2544–2550.

[26] Imbuldeniya AM, Jiwa N, Murphy JP. Bilateral atypical insufficiency fractures of the proximal tibia and a unilateral distal femoral fracture with long-term intravenous bisphosphonate therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2012; 6: 50.

[27] Daffner RH, Pavlov H. Stress fractures: current concepts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 159: 245–252.

[28] Matcuk GR, Mahanty SR, Skalski MR, et al. Stress fractures: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2016; 23: 365–375.

[29] Brukner P, Bradshaw C, Khan KM, et al. Stress fractures: a review of 180 cases. Clin J Sport Med 1996; 6: 85–89.

[30] Ohta-Fukushima M, Mutoh Y, Takasugi S, et al. Characteristics of stress fractures in young athletes under 20 years. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2002; 42: 198.

[31] Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 8580–8587.

[32] Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 1567–1575.

[33] Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Systemic review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med 2006; 145: 235]. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 753–761.

[34] McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med 2013; 126: 13–20.

[35] US Food and Drug Administration. Information on bisphosphonates (marketed as Actonel, Actonel +Ca, Aredia, Boniva, Didronel, Fosamax, Fosamax+D, Reclast, Skelid, and Zometa). (2008, accessed 15 December 2022).

[36] Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al.; HORIZON Pivotal Fracture Trial. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1809–1822.

[37] Cummings SR, Schwartz AV, Black DM. Alendronate and atrial fibrillation [letter]. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 1895–1896.

[38] Heckbert SR, Li G, Cummings SR, et al. Use of alendronate and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 826–831.

[39] Rogers-Smith E, Whitley N, Elwood C, et al. Suspected bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a cat being treated with alendronate for idiopathic hypercalcaemia. Vet Rec Case Rep 2019; 7.

[40] Piermattei DL, Johnson DL. The pelvis and hip joint. In: Piermattei DL, Johnson KA. (eds). An atlas of surgical approaches to the bones and joints of the dog and cat. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2004, pp 370–373.

[41] Capeci CM, Tejwani NC. Bilateral low-energy simultaneous or sequential femoral fractures in patients on long-term alendronate therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91: 2556–2561.

[42] Cantatore M, Clements DN. Bilateral calcaneal stress fractures in two cats. J Small Anim Pract 2015; 56: 417–421.

[43] Pienkowski D, Wood CL, Malluche HH. Trabecular bone microcrack accumulation in patients treated with bisphosphonates for durations up to 16 years. J Orthop Res 2023; 41: 1033–1039.

[44] Khan SA, Kanis JA, Vasikaran S, et al. Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 1997; 12: 1700–1707.

[45] Lin JH. Bisphosphonates: a review of their pharmacokinetic properties. Bone 1996; 18: 75–85.

[46] Reddy MS, Weatherford TW, Smith A, et al. Alendronate treatment of naturally-occurring periodontitis in beagle dogs. J Periodontol 1995; 66: 211–217.

[47] Mohn KL, Jacks TM, Schleim KD, et al. Alendronate binds to tooth root surfaces and inhibits progression of feline tooth resorption: a pilot proof-of-concept study. J Vet Dent 2009; 26: 74–81.

[48] Fan TM, de Lorimier LP, Garrett LD, et al. The bone biologic effects of zoledronate in healthy dogs and dogs with malignant osteolysis. J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 380–387.

[49] Oblak ML, Boston SE, Higginson G, et al. The impact of pamidronate and chemotherapy on survival times in dogs with appendicular primary bone tumors treated with palliative radiation therapy. Vet Surg 2012; 41: 430–435.

[50] Wypij JM, Heller DA. Pamidronate Disodium for palliative therapy of feline bone-invasive tumors. Vet Med Int 2014; 2014.

[51] Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, et al. Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. J Bone Miner Res 2000; 15: 613–620.

[52] Burr DB, Allen MR. Mandibular necrosis in beagle dogs treated with bisphosphonates. Orthod Craniofac Res 2009; 12: 221–228.

[53] Burr DB, Miller L, Grynpas M, et al. Tissue mineralization is increased following 1-year treatment with high doses of bisphosphonates in dogs. Bone 2003; 33: 960–969.

[54] Waters RV, Gamradt SC, Asnis P. Systemic corticosteroids inhibit bone healing in a rabbit ulnar osteotomy model. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71: 316–321.

[55] Aaron JE, Francis RM, Peacock M, et al. Contrasting microanatomy of idiopathic and corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; 243: 294–305.

[56] LoCascio V, Bonucci E, Imbimbo B, et al. Bone loss in response to long-term glucocorticoid therapy. Bone Miner 1990; 8: 39–51.

[57] Lukert B, Kream BE. Clinical and basic aspects of glucocorticoid action in bone. In: Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA. (eds). Principles of bone biology. New York: Academic Press, 1996, pp 533–548.

[58] Langley-Hobbs S. Patella fracture in cats with persistent deciduous teeth knees and teeth syndrome (KaTS). Comp Anim 2016; 21: 620–626.

[59] Langley-Hobbs SJ. Survey of 52 fractures of the patella in 34 cats. Vet Rec 2009; 164: 80–86.

[60] Langley-Hobbs SJ, Ball S, Mckee WM. Transverse stress fractures of the proximal tibia in 10 cats with non-union patellar fractures. Vet Rec 2009; 164: 425–430.

[61] Reyes NA, Longley M, Bailey S, et al. Incidence and types of preceding and subsequent fractures in cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 750–764.

[62] Howes C, Longley M, Reyes N, et al. Skull pathology in 10 cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 793–800.

[63] Morris AP, Anderson AA, Barnes DM, et al. Plate failure by bending following tibial fracture stabilisation in 10 cats. J Small Anim Pract 2016; 57: 472–478.

[64] Craig A, Witte PG, Moody T, et al. Management of feline tibial diaphyseal fractures using orthogonal plates performed via minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 6–14.

[65] Marturello DM, Perry KL, Déjardin LM. Clinical application of the small I-Loc interlocking nail in 30 feline fractures: a prospective study. Vet Surg 2021; 50: 588–599.