| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:短毛猫 |

| 年龄:7岁 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:是 | |

| 诊断:脊柱弓形虫肉芽肿 | |

01 主诉及病史

渐进性后肢共济失调。当地兽医检查时的脊柱X光、血液学和生化检查均无异常。使用美洛昔康(0.1 mg/kg,q24h口服),连续数周后症状未改善。

该猫一直定期接种疫苗和驱虫。就诊时身体状况良好,既往无疾病。由于这只猫可以到户外活动,因此无法排除外伤的可能性,但也没有观察到明显的外伤。

02 检查

全身体检未发现异常。神经系统检查显示患者有中度后肢共济失调。肢体感觉和脊柱反射正常。胸腰交界处的脊柱触诊疼痛。没有颅神经损伤或行为异常。

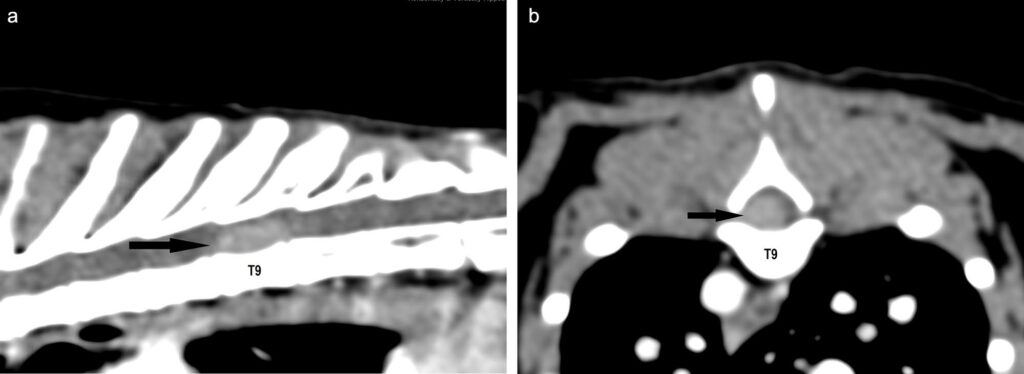

脊柱CT扫描在T9水平发现一个硬膜外、左外侧、界限清楚、椭圆形和中度增强的软组织衰减性肿块(下图)。肿块占据了约三分之二的椎管,导致脊髓受到严重压迫。肿块大小为4.5×3.5×9.3 mm。T9椎体无骨性反应。

03 治疗

起初猫主人拒绝了手术治疗,并继续使用美洛昔康口服。由于神经症状不断加重,主人同意5天后实施手术。

术前复查CT,显示T9硬膜外肿块增大,大小为4.9×3.7×11 mm,导致脊髓受压更加严重。在T8-T10水平进行了左侧减压半椎板切除术。术中,肿块位于T9水平,表现为左侧均质非骨性硬膜外肿块,导致脊髓严重受压。肿块没有明显的包膜,由于质地非常易碎,只能零星切除。对肿块进行了尽可能多的剥离,但无法将其全部切除。

术后一直住院治疗。使用阿莫西林-克拉维酸(20 mg/kg,q24h静注),马洛比坦(1 mg/kg,q24h静注),丁丙诺啡(20 µg/kg,q8h静注),甲脒唑钠(50 mg/kg皮下注射),泼尼松龙(0.8 mg/kg,q24h口服),并持续输注等渗晶体液3 mL/kg/h。

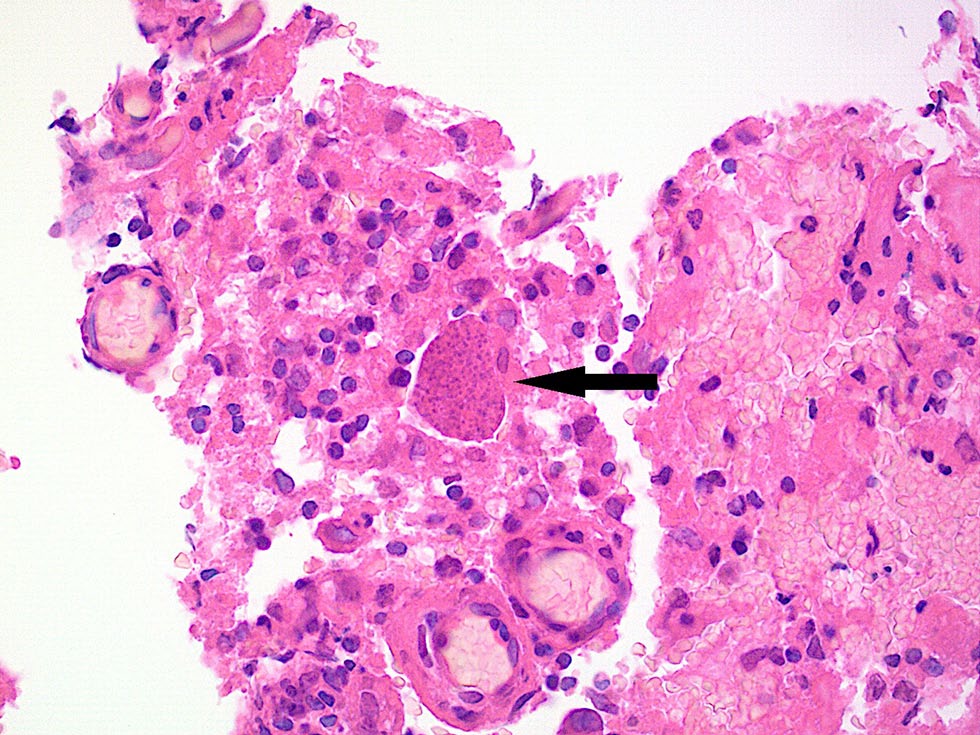

组织病理学检查显示,嗜酸性细胞中夹杂着多个淋巴细胞、浆细胞以及一些粒细胞和巨噬细胞。还可发现穿插的较小血管切口以及孤立的坏死。此外,还能发现个别球状结构或囊性结构,内含颗粒状内容物(下图)。

经组织病理学检查,诊断为弓形虫病引起的高级别混合细胞、慢性化脓性和坏死性、部分肉芽肿性炎症。随后,血液检测和免疫荧光抗体测定证实,IgM-IFT阴性,IgG-IFT强阳性,数值大于1:1024。随后对肉芽肿组织进行的PCR 检测也显示弓形虫(T. gondii)阳性。

04 预后

根据组织病理学和实验室结果,治疗改为克林霉素(22 mg/kg,q12h口服,连续6周)。5天后停用泼尼松龙,48小时后再服用美洛昔康(0.1 mg/kg,q24h口服,共2周)。

出院5周后复查,主人说神经功能最初有所改善,但后来效果缓慢。检查发现轻微的后肢共济失调,四肢本体感觉和脊柱反射均无障碍。由于后肢共济失调仍在持续,而且主人担心肉芽肿会残留、压迫或复发,因此再次进行了CT扫描。

CT扫描显示T9位置的左侧硬膜外腔有一个小的增强型软组织病变,大小为0.8×3.4×7 mm,导致脊髓左侧轻度受压。在左侧半椎板切除术区域和沿T9椎棘突的左外侧(手术入路)也显示出软组织的对比增强。

随后,主人通过电话告知猫的最新情况,步态逐渐得到改善,但仍存在轻微的步态异常。 手术9个月后,神经状况急剧恶化,在主人的要求下,猫被安乐死,没有接受进一步的临床评估。主人拒绝进行尸检。

05 讨论

猫后肢共济失调最常见的病因是炎症/感染或肿瘤性脊柱疾病。较少见的病因是外伤、先天性、血管和退行性或代谢/消化系统疾病[1-3]。

弓形虫病是一种常见的猫科寄生虫病,可导致中枢神经障碍,被认为是猫中枢神经系统最重要的寄生虫病之一[4-8]。本报告描述了一例经组织病理学和PCR证实的猫脊柱弓形虫肉芽肿病例。

根据Marioni-Henry的研究[1,2],猫脊柱感染性疾病发病率为32%。另一项对猫脊柱疑似疾病进行核磁共振检查的研究显示,炎症/感染性疾病的发病率为14%[7]。弓形虫感染被认为是猫中枢神经系统第二大常见的寄生虫病,占中枢神经疾病的6%[2,4,5,8]。然而,本病例是首例猫脊柱弓形虫肉芽肿的报道。

所有哺乳动物都可能感染弓形虫。猫是唯一的确定宿主,而其他温血动物则被视为中间宿主。感染可通过腹腔感染和乳头感染,也可通过口服卵囊或其他发育阶段感染,例如,通过受感染的中间宿主、水、植物或土壤感染。寄生虫最常见的进入途径被认为是通过摄入受感染的中间宿主[6,9-11]。

脊柱硬膜外肉芽肿并非由弓形虫引起,而是由其他多种感染性病原体引起的,如隐球菌、无形体、荚膜组织胞浆菌和微分枝杆菌等[27,30-34]。为了确定这只猫硬膜外软组织肿块的病因,对其进行了减压半椎板切除术并采集了组织样本。

虽然肿块占据了约三分之二的椎管,但该猫仅表现出轻微的神经症状,与一些已报道的因寄生虫病引起的硬膜外脊柱肉芽肿相似[31,32]。与脊髓严重受压有关的是,可能会出现更严重的神经功能缺损。由此推断,脊髓受压的时间较长,因此神经组织可能会慢慢适应。

一旦确诊为弓形虫病,就推荐开始使用克林霉素进行抗生素治疗[35]。病毒性疾病对临床弓形虫病的影响尚存争议。有证据表明,猫白血病病毒(FeLV)或猫免疫缺陷病毒(FIV)感染可诱发急性全身性弓形虫病[36-39]。

这只猫没有接受检测,因为它定期接种了FeLV和FIV疫苗。然而,回过头来看,如果同时存在对免疫系统有影响的传染病,就会引起弓形虫易感的可能。此外,特别是对于猫来说,由于神经系统疾病通常是由感染引起的,因此一般应进行全面的脑脊液分析[40]。

MRI被认为是诊断中枢神经系统疾病的首选工具[41]。相比之下,CT目前在骨骼结构成像方面优于MRI。由于脊柱肿瘤通常伴有骨质病变,而本医院没有MRI,因此对该病例进行了CT 扫描[42]。

不幸的是,这只猫在术后9个月出现了明显的神经功能衰退,在没有进一步诊断的情况下被安乐死。根据术后5周CT扫描显示硬膜外软组织肿块复发的证据,肿块很可能发生了临床意义上的再生。

回过头来看,在复查CT时重复测定抗体可能会有意义。更敏感的方法是分析脑脊液或对之前肉芽肿位置进行细针穿刺[35]。为了延长患者的存活时间并避免出现临床症状,可以考虑再次进行手术或单独使用克林霉素或使用第二种抗弓形虫药物。

参考文献

1. Marioni-Henry K. Feline spinal cord diseases. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40: 1011–1028.

2. Marioni-Henry K, Vite CH, Newton AL, et al. Prevalence of diseases of the spinal cord of cats. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18: 851–858.

3. Mella SL, Cardy TJ, Volk HA, et al. Clinical reasoning in feline spinal disease: which combination of clinical information is useful? J Feline Med Surg 2020; 22: 521–530.

4. Singh M, Foster D, Child G, et al. Inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid analysis in cats: clinical diagnosis and outcome. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 77–93.

5. Negrin A, Lamb CR, Cappello R, et al. Results of magnetic resonance imaging in 14 cats with meningoencephalitis. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 109–116.

6. Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM. Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 2019; 6.

7. Gonçalves R, Platt SR, Llabrés-Díaz FJ, et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings in 92 cats with clinical signs of spinal cord disease. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 53–59.

8. Bradshaw J, Pearson G, Gruffydd-Jones T. A retrospective study of 286 cases of neurological disorders of the cat. J Comp Pathol 2004; 131: 112–120.

9. López Ureña NM, Chaudhry U, Calero Bernal R, et al. Contamination of soil, water, fresh produce, and bivalve mollusks with Toxoplasma gondii oocysts: a systematic review. Microorganisms 2022; 10.

10. Lappin MR. Update on the diagnosis and management of Toxoplasma gondii infection in cats. Top Companion Anim Med 2010; 25: 136–141.

11. Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Lappin MR. Toxoplasmosis and other intestinal coccidial infections in cats and dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009; 39: 1009–1034.

12. Vollaire MR, Radecki SV, Lappin MR. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in clinically ill cats in the United States. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 874–877.

13. Montazeri M, Galeh TM, Moosazadeh M, et al. The global serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in felids during the last five decades (1967–2017): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors 2020; 13: 82.

14. Dubey J, Carpenter J. Histologically confirmed clinical toxoplasmosis in cats: 100 cases (1952-1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993; 203: 1556–1566.

15. Dubey J, Cerqueira-Cézar C, Murata F, et al. All about toxoplasmosis in cats: the last decade. Vet Parasitol 2020; 283.

16. Cohen TM, Blois S, Vince AR. Fatal extraintestinal toxoplasmosis in a young male cat with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. Can Vet J 2016; 57: 483–486.

17. Peterson J, Willard M, Lees G, et al. Toxoplasmosis in two cats with inflammatory intestinal disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991; 199: 473–476.

18. McConnell JF, Sparkes AH, Blunden AS, et al. Eosinophilic fibrosing gastritis and toxoplasmosis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 82–88.

19. Simpson KE, Devine BC, Gunn-Moore D. Suspected toxoplasma-associated myocarditis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 203–208.

20. Butts DR, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Lameness, generalised myopathy and myalgia in an adult cat with toxoplasmosis. J Feline Med Surg 2020; 6.

21. McKenna M, Augusto M, Suárez-Bonnet A, et al. Pulmonary mass-like lesion caused by Toxoplasma gondii in a domestic shorthair cat. J Vet Intern Med 2021; 35: 1547–1550.

22. Anfray P, Bonetti C, Fabbrini F, et al. Feline cutaneous toxoplasmosis: a case report. Vet Dermatol 2005; 16: 131–136.

23. Kul O, Atmaca HT, Deniz A, et al. Clinicopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous toxoplasmosis in an Angora cat. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2011; 124: 386–389.

24. Park C-H, Ikadai H, Yoshida E, et al. Cutaneous toxoplasmosis in a female Japanese cat. Vet Pathol 2007; 44: 683–687.

25. Lindsay SA, Barrs VR, Child G, et al. Myelitis due to reactivated spinal toxoplasmosis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 818–821.

26. Dubey J, Fenner W. Clinical segmental myelitis associated with an unidentified toxoplasma-like parasite in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 1993; 5: 472–480.

27. Alves L, Gorgas D, Vandevelde M, et al. Segmental meningomyelitis in 2 cats caused by Toxoplasma gondii. J Vet Intern Med 2011; 25: 148–152.

28. Pfohl JC, Dewey CW. Intracranial Toxoplasma gondii granuloma in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 369–374.

29. Falzone C, Baroni M, De Lorenzi D, et al. Toxoplasma gondii brain granuloma in a cat: diagnosis using cytology from an intraoperative sample and sequential magnetic resonance imaging. J Small Anim Pract 2008; 49: 95–99.

30. Mari L, Shelton GD, De Risio L. Distal polyneuropathy in an adult Birman cat with toxoplasmosis. J Feline Med Surg 2016; 2.

31. Belluco S, Thibaud J, Guillot J, et al. Spinal cryptococcoma in an immunocompetent cat. J Comp Pathol 2008; 139: 246–251.

32. Foureman P, Longshore R, Plummer SB. Spinal cord granuloma due to Coccidioides immitis in a cat. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19: 373–376.

33. Martín-Ambrosio Francés M, Pradel J, Domínguez E, et al. Clinical resolution of systemic mycobacterial infection in a cat with a suspected spinal granuloma. Vet Rec Case Rep 2023.

34. Vinayak A, Kerwin SC, Pool RR. Treatment of thoracolumbar spinal cord compression associated with Histoplasma capsulatum infection in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007; 230: 1018–1023.

35. Hartmann K, Addie D, Belák S, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 631–637.

36. Heidel J, Dubey J, Blythe L, et al. Myelitis in a cat infected with Toxoplasma gondii and feline immunodeficiency virus. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990; 196: 316–318.

37. Davidson M, Rottman J, English R, et al. Feline immunodeficiency virus predisposes cats to acute generalized toxoplasmosis. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 1486–1497.

38. Dorny P, Speybroeck N, Verstraete S, et al. Serological survey Toxoplasma gondii of a on feline immunodeficiency virus and feline leukaemia virus in urban stray cats in Belgium. Vet Rec 2002; 151: 626–629.

39. Pena HFdJ, Evangelista CM, Casagrande RA, et al. Fatal toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed domestic cat from Brazil caused by Toxoplasma gondii clonal type I. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26: 177–184.

40. Gunn-Moore DA, Reed N. CNS disease in the cat: current knowledge of infectious causes. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 824–836.

41. Lane B. Practical imaging of the spine and spinal cord. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2003; 14: 438–443.

42. da Costa RC, Samii VF. Advanced imaging of the spine in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40: 765–790.