| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:短毛猫 |

| 年龄:21个月 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:否 | |

| 诊断:弓形虫肺炎 | |

01 主诉及病史

在家中突发呼吸急促和呼吸困难。

就诊前两天出现了急性腹泻和厌食,并逐渐变得嗜睡。三个月前诊断为原发性自身免疫性溶血性贫血(AIHA),接受了环孢素(5 mg/kg PO q12h)单药治疗,之后又联合泼尼松龙(开始剂量为1.4 mg/kg PO q12h),逐渐减少(每2-3周减少25%),并在发病两周前停药。

该猫严格饲养在室内,没有服用其他药物或补充剂。没有接种最新的疫苗,但一直定期驱虫。在确诊AIHA时,猫白血病病毒和猫免疫缺陷病毒呈阴性。

02 检查

心率160次/分,呼吸68次/分(腹部用力呼吸),无法测量直肠体温。口腔黏膜苍白,毛细血管再充盈时间小于2秒。腹部和外周淋巴结触诊无异常。

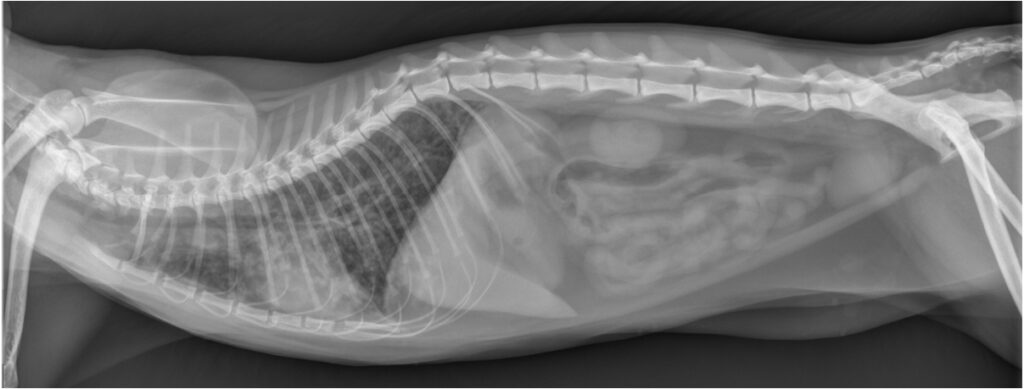

腹部超声显示肝脏、脾脏、肾脏、肾上腺、胰腺、肝脏、胆囊、胃和肠道均未发现异常,但肠系膜淋巴结轻度肿大。X光片显示肺野混浊度普遍降低,支气管间质与肺泡混合型,心脏轮廓不清晰,椎心大小(VHS)轻度增大至9.4(<8.1)(下图)。

血细胞比容:37.3%(30.3-52.3)

平均血球容积:38.0 fL(35.9-53.1)

平均血红蛋白:13.4 pg(11.8-17.3)

网织红细胞计数:13.7 × 10^9/L(<50)

白细胞↓:0.81×10^9/L(2.87-17.02)

中性粒细胞↓:0.13×10^9/L(1.48-10.29)

血小板↓:137×10^9/L(151-600)

血糖:8.2 mmol/L(3.9-8.2)

血钾:3.5 mmol/L(3.4-4.6)

血钠校正氯化物↑:120.2 mmol/L(107-120)

NT-proBNP正常,肺蠕虫阴性,猫血支原体、无形体和犬埃里希氏体均为阴性。弓形虫血清学检测显示IgM阴性,IgG呈阳性(>1:1024)。

考虑在全麻下进行气管支气管镜检查和支气管肺泡灌洗等更具侵入性的诊断。但考虑到猫的整体状况,这些检查无法进行。

03 治疗

送入重症监护室,补充氧气(氧气笼,40%氧气)、静脉输液(林格醋酸盐溶液)、茶碱注射扩张支气管,继续使用环孢素治疗AIHA。

鉴于严重的中性粒细胞减少和24小时内临床症状无明显改善,加用克林霉素。

04 预后

住院三天后病情稳定,但呼吸急促。

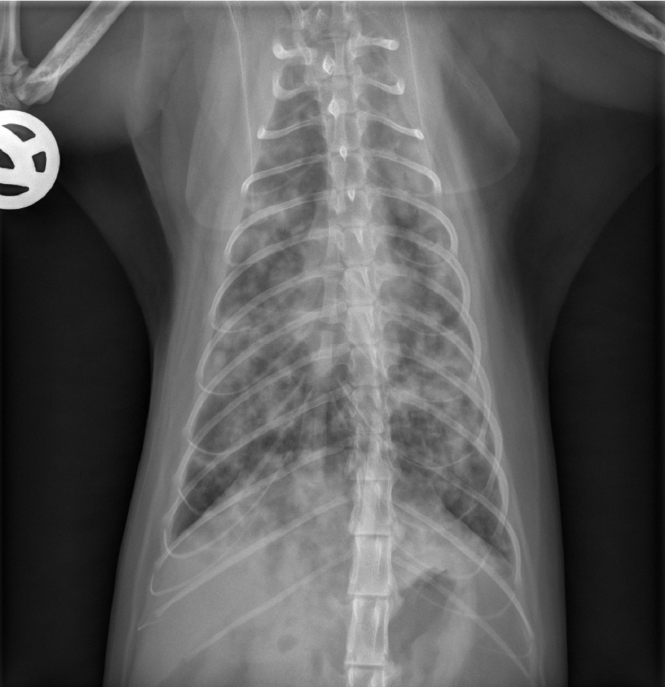

住院第四天出现急性呼吸困难。复查胸部X光片发现病情有轻度进展(下图)。

猫出现急性衰竭,主人选择了安乐死。

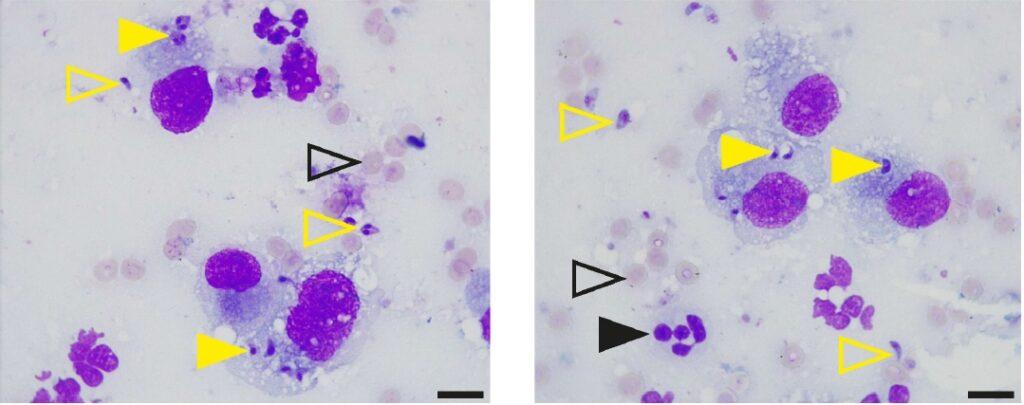

死后对肺部进行了气管支气管肺泡灌洗和细针穿刺。细胞学检查显示,许多寄生虫结构的物质分布在细胞外和肺泡巨噬细胞内(下图)。对寄生虫DNA进行微卫星分型后,确定为弓形虫II型TgM-A变异体。

05 讨论

自身免疫性疾病在包括猫在内的宠物中很常见,可能涉及多个器官系统,也可能表现为多中心性疾病,如系统性红斑狼疮[1]。狗和猫在发病频率、潜在病因和病理机制方面存在差异,而免疫反应(尤其是T辅助细胞平衡)方面的物种特异性差异也是造成这两个物种之间存在某些差异的原因之一[2]。

免疫介导的溶血性贫血在猫中很常见[3],需要排除非免疫介导的原因[4-9]、感染性病因(如溶血性支原体)和肿瘤性病因(如淋巴瘤)才能诊断为原发性自身免疫性溶血性贫血(AIHA)[10]。

AIHA治疗的主要方法是免疫抑制和预防血栓形成和血栓栓塞等并发症[3,11,12]。继发性感染也是自然或先天性免疫抑制患者需要关注的问题[13,14],包括感染性细菌或原虫肺炎以及可能导致致命后果的败血症[15]。

弓形虫(T. gondii)是一种细胞内寄生虫,猫是其最终宿主,所有温血动物都是中间宿主[16]。它可导致人畜共患病弓形虫病。最近的两项系统分析发现,人类血清阳性反应率约为26%[17],家猫血清阳性反应率约为35% [18]。欧洲观察到的大多数弓形虫基因型属于三个克隆系(Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型和Ⅲ型),其中Ⅱ型代表了绝大多数。

弓形虫在其生命周期中有几个发育阶段[19]。寄生虫在宿主肠道内进行有性繁殖,产生的卵囊随粪便排出体外。口服会导致急性期(速生虫)迅速无性繁殖,然后通过血液、淋巴和腹腔液感染所有组织[20]。

在疾病的慢性阶段,细胞内囊肿与裂殖体形成,裂殖体的新陈代谢减弱,可能终生存在于宿主体内[21]。在健康和免疫功能正常的成年人中,弓形虫感染通常没有症状。然而,对于因自身免疫性疾病治疗或潜在疾病(如人类免疫缺陷病毒)而导致免疫抑制的人来说,弓形虫感染可能会产生严重的影响[22-25]。

同样,猫的局部或播散性弓形虫病也与使用免疫抑制剂治疗后的免疫缺陷状态有关 [26-29]或与逆转录病毒感染有关[30,31]。相应的临床症状包括发烧、食欲不振、体重减轻、嗜睡、神经症状(如震颤或抽搐)、肺炎、葡萄膜炎、视网膜炎和肝炎。

鉴于猫弓形虫病的临床表现范围很广,因此诊断猫弓形虫病通常具有挑战性,如果病例一直得不到诊断,就会导致致命的后果。本病例报告记录了一只猫在接受免疫抑制治疗后,潜伏的弓形虫重新活化,并在呼吸系统出现临床表现。

本病例使用直接检测(即细胞学和微卫星基因分型)来确认弓形虫病,特别是根据其在呼吸系统的表现。肺泡灌洗液的显微镜检查显示存在大量原生动物结构,证实了呼吸道弓形虫病的怀疑。微卫星分析证实切片中存在弓形虫,并进一步将其归类为II型弓形虫,这是欧洲和北美人类和家畜中的主要弓形虫类型[36]。

总之,这些结果证实了这只猫感染性肺炎的诊断,并确定弓形虫为主要病原体。在免疫力低下的人群中,弓形虫的再活化通常表现为脑炎,较少见的表现为肺炎、视网膜炎或全身播散性疾病[15,25,37]。本发现证实了之前关于猫的报道,即猫在接受免疫抑制剂(如泼尼松龙和环孢素)治疗后可能导致急性弓形虫病[26-29,34,35]。

参考文献

[1] Gershwin, L.J. Current and Newly Emerging Autoimmune Diseases. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 323–338.

[2] Day, M.J. Cats are not small dogs: Is there an immunological explanation for why cats are less affected by arthropod-borne disease than dogs? Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 507.

[3] Kohn, B.; Weingart, C.; Eckmann, V.; Ottenjann, M.; Leibold, W. Primary immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in 19 cats: Diagnosis, therapy, and outcome (1998–2004). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 159–166.

[4] Kohn, B.; Goldschmidt, M.H.; Hohenhaus, A.E.; Giger, U. Anemia, splenomegaly, and increased osmotic fragility of erythrocytes in Abyssinian and Somali cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 217, 1483–1491.

[5] Grahn, R.A.; Grahn, J.C.; Penedo, M.C.; Helps, C.R.; Lyons, L.A. Erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency mutation identified in multiple breeds of domestic cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 207.

[6] Hurwitz, B.M.; Center, S.A.; Randolph, J.F.; McDonough, S.P.; Warner, K.L.; Hazelwood, K.S.; Chiapella, A.M.; Mazzei, M.J.; Leavey, K.; Acquaviva, A.E.; et al. Presumed primary and secondary hepatic copper accumulation in cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 244, 68–77.

[7] Kushida, K.; Giger, U.; Tsutsui, T.; Inaba, M.; Konno, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Noguchi, K.; Yabuki, A.; Mizukami, K.; Kohyama, M.; et al. Real-time PCR genotyping assay for feline erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency and mutant allele frequency in purebred cats in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2015, 77, 743–746.

[8] DeAvilla, M.D.; Leech, E.B. Hypoglycemia associated with refeeding syndrome in a cat. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2016, 26, 798–803.

[9] Yu, J.; Jenkins, E.; Podadera, J.M.; Proschogo, N.; Chan, R.; Boland, L. Zinc toxicosis in a cat associated with ingestion of a metal screw nut. JFMS Open Rep. 2022, 8, 20551169221136464.

[10] Garden, O.A.; Kidd, L.; Mexas, A.M.; Chang, Y.M.; Jeffery, U.; Blois, S.L.; Fogle, J.E.; MacNeill, A.L.; Lubas, G.; Birkenheuer, A.; et al. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs and cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 313–334.

[11] Yoshida, T.; Mandour, A.S.; Sato, M.; Hirose, M.; Kikuchi, R.; Komiyama, N.; Hendawy, H.A.; Hamabe, L.; Tanaka, R.; Matsuura, K.; et al. Pulmonary thromboembolism due to immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in a cat: A serial study of hematology and echocardiographic findings. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 930210.

[12] DeLaforcade, A.; Bacek, L.; Blais, M.C.; Boyd, C.; Brainard, B.M.; Chan, D.L.; Cortellini, S.; Goggs, R.; Hoareau, G.L.; Koenigshof, A.; et al. 2022 Update of the Consensus on the Rational Use of Antithrombotics and Thrombolytics in Veterinary Critical Care (CURATIVE) Domain 1-Defining populations at risk. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2022, 32, 289–314.

[13] Schmiedt, C.W.; Holzman, G.; Schwarz, T.; McAnulty, J.F. Survival, complications, and analysis of risk factors after renal transplantation in cats. Vet. Surg. 2008, 37, 683–695.

[14] Swann, J.W.; Szladovits, B.; Glanemann, B. Demographic Characteristics, Survival and Prognostic Factors for Mortality in Cats with Primary Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 147–156.

[15] Mariuz, P.; Bosler, E.M.; Luft, B.L. Toxoplasma pneumonia. Semin. Respir. Infect. 1997, 12, 40–43.

[16] Tenter, A.M.; Heckeroth, A.R.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: From animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000, 30, 1217–1258.

[17] Molan, A.; Nosaka, K.; Hunter, M.; Wang, W. Global status of Toxoplasma gondii infection: Systematic review and prevalence snapshots. Trop. Biomed. 2019, 36, 898–925.

[18] Montazeri, M.; Mikaeili Galeh, T.; Moosazadeh, M.; Sarvi, S.; Dodangeh, S.; Javidnia, J.; Sharif, M.; Daryani, A. The global serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in felids during the last five decades (1967–2017): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 82.

[19] Dubey, J.P.; Lindsay, D.S.; Speer, C.A. Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 267–299.

[20] Halonen, S.K.; Weiss, L.M. Toxoplasmosis. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 114, 125–145.

[21] Weiss, L.M.; Kim, K. The development and biology of bradyzoites of Toxoplasma gondii. Front. Biosci. 2000, 5, 391–405.

[22] Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976.

[23] Robert-Gangneux, F.; Belaz, S. Molecular diagnosis of toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 29, 330–339.

[24] Dunay, I.R.; Gajurel, K.; Dhakal, R.; Liesenfeld, O.; Montoya, J.G. Treatment of Toxoplasmosis: Historical Perspective, Animal Models, and Current Clinical Practice. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00057-17.

[25] Wang, Z.D.; Liu, H.H.; Ma, Z.X.; Ma, H.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Yang, Z.B.; Zhu, X.Q.; Xu, B.; Wei, F.; Liu, Q. Infection in Immunocompromised Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 389.

[26] Lo Piccolo, F.; Busch, K.; Palic, J.; Geisen, V.; Hartmann, K.; Unterer, S. Toxoplasma gondii-associated cholecystitis in a cat receiving immunosuppressive treatment. Tierärztliche Prax. Ausg. K Kleintiere/Heim. 2019, 47, 453–457.

[27] Salant, H.; Klainbart, S.; Kelmer, E.; Mazuz, M.L.; Baneth, G.; Aroch, I. Systemic toxoplasmosis in a cat under cyclosporine therapy. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2021, 23, 100542.

[28] Pena, H.F.D.; Evangelista, C.M.; Casagrande, R.A.; Biezus, G.; Wisser, C.S.; Ferian, P.E.; de Moura, A.B.; Rolim, V.M.; Driemeier, D.; Oliveira, S.; et al. Fatal toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed domestic cat from Brazil caused by clonal type I. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 26, 177–184.

[29] Ludwig, H.C.; Schlicksup, M.D.; Beale, L.M.; Aronson, L.R. Toxoplasma gondii infection in feline renal transplant recipients: 24 cases (1998–2018). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2021, 258, 870–876.

[30] Moore, A.; Burrows, A.K.; Malik, R.; Ghubash, R.M.; Last, R.D.; Remaj, B. Fatal disseminated toxoplasmosis in a feline immunodeficiency virus-positive cat receiving oclacitinib for feline atopic skin syndrome. Vet. Dermatol. 2022, 33, 435–439.

[31] Davidson, M.G.; Rottman, J.B.; English, R.V.; Lappin, M.R.; Tompkins, M.B. Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Predisposes Cats to Acute Generalized Toxoplasmosis. Am. J. Pathol. 1993, 143, 1486–1497.

[32] Ajzenberg, D.; Collinet, F.; Mercier, A.; Vignoles, P.; Darde, M.L. Genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii isolates with 15 microsatellite markers in a single multiplex PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 4641–4645.

[33] Joeres, M.; Cardron, G.; Passebosc-Faure, K.; Plault, N.; Fernandez-Escobar, M.; Hamilton, C.M.; O’Brien-Anderson, L.; Calero-Bernal, R.; Galal, L.; Luttermann, C.; et al. A ring trial to harmonize Toxoplasma gondii microsatellite typing: Comparative analysis of results and recommendations for optimization. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 803–818.

[34] Barrs, V.R.; Martin, P.; Beatty, J.A. Antemortem diagnosis and treatment of toxoplasmosis in two cats on cyclosporin therapy. Aust. Vet. J. 2006, 84, 30–35.

[35] Last, R.D.; Suzuki, Y.; Manning, T.; Lindsay, D.; Galipeau, L.; Whitbread, T.J. A case of fatal systemic toxoplasmosis in a cat being treated with cyclosporin A for feline atopy. Vet. Dermatol. 2004, 15, 194–198.

[36] Szabo, E.K.; Finney, C.A. Toxoplasma gondii: One Organism, Multiple Models. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 113–127.

[37] Walker, M.; Zunt, J.R. Parasitic central nervous system infections in immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1005–1015.