| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:短毛猫 |

| 年龄:10岁 | |

| 性别:雄 | |

| 是否绝育:是 | |

| 诊断:骨关节炎 | |

01 主诉及病史

因左后肢跛行就诊。在5个月大时曾有过右后肢趾骨粉碎性骨折和滑脱的病史,当时在右后肢股骨近端三分之一处进行了截肢,保留了右侧髋关节。

02 检查

身体状况评分5/9。整体活动能力严重受限,行走两三步就坐下。左侧髋关节运动时,尤其是伸展时,会感到明显疼痛,活动范围缩小。对右侧髋关节的任何触诊和操作都会引起反感。右肘内侧中度肿胀。未发现其他明显异常。

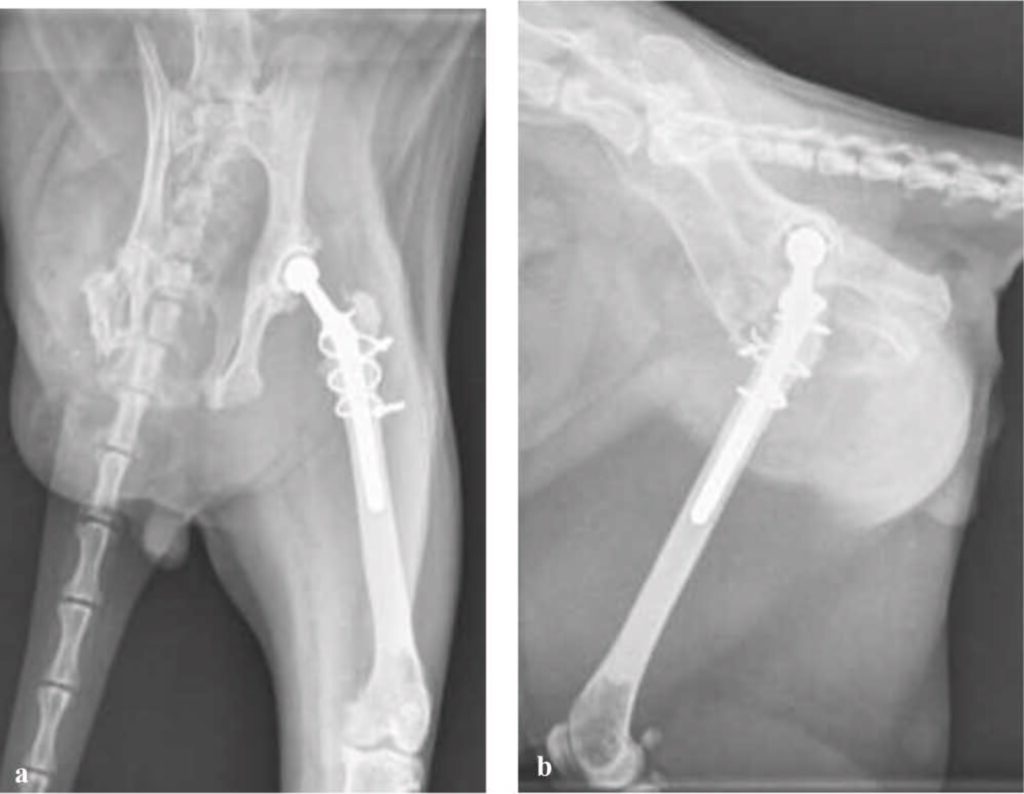

用盐酸右美托咪定(5 μg/kg IV)和丁诺啡醇(0.3 mg/kg IV)进行镇静并进行了X线检查(下图)。X光片显示左、右髋关节骨关节炎明显,关节周围骨质增生。肘部X光片显示右肘内侧有中度新骨形成,提示屈肌腱粘连,双肘关节周围骨质变化符合骨关节炎。

根据这些临床和影像学检查结果,在与主人讨论后,决定实施左后肢全髋关节置换术。拟7周后返回医院接受手术。

03 手术

使用盐酸右美托咪定(5 μg/kg IV)和美沙酮(0.2 mg/kg IV)进行预处理,并使用丙泊酚(1 mg/kg IV)进行麻醉,使用2%异氟醚维持麻醉。

切开皮肤前30分钟注射头孢呋辛(20 mg/kg),之后每隔90分钟重复注射一次。硬膜外镇痛使用布比卡因(1 mg/kg)。

按常规入路进行了全髋关节置换术,并置入了12 mm骨水泥固定(CFX)髋臼杯。其目的是将髋臼杯放置在比正常位置更封闭的位置,以减少因对侧后肢截肢而造成的髋关节外翻。

在股骨通道扩孔过程中,发现股骨近端内侧有一个很小的裂缝。为避免裂口扩大,在股骨近端使用了三根直径为1 mm(20 G)的矫形钢丝进行固定。在用骨水泥填充股骨通道后,使用3 mm的CFX骨干。选择了+2股骨头,以最大限度地减少股骨头与髋臼接口处的松弛。常规进行伤口闭合。术后拍摄了髋关节的X光片(下图)。

04 预后

接下来的48小时内住院治疗,美沙酮0.2 mg/kg q4h用于镇痛。术后24小时内每8小时静脉注射一次头孢呋辛(20 mg/kg)。住院期间皮下注射罗贝拉昔布(每次1 mg/kg,q24h)持续3天,然后在家继续口服。术后口服头孢氨苄(20 mg/kg)5天。

术后6周,X线结果显示植入物稳定,骨愈合顺利(下图)。

术后未出现并发症(随访30个月)。使用猫肌肉骨骼疼痛指数来跟踪术后活动能力,结果显示总指数有所上升,提示活动能力改善(从术后6周的45分上升到术后15个月的58分)。

05 讨论

髋关节疾病和损伤在猫中很常见[1-3]。全髋关节置换术(THR)是治疗人和小型动物髋关节衰弱的金标准疗法[4-7]。在一项对9只接受THR的后肢截肢犬进行的回顾性病例系列研究中,对侧后肢截肢被认为是THR的相对禁忌症,因为该研究中报告的并发症升高[8]。

有三项研究[8,11,12]对曾接受过对侧后肢截肢的犬进行的THR进行了描述,其中一项研究报告称,4/9的犬在THR后出现关节松动,需要进行手术翻修[8]。

另一项研究包括16只后肢截肢的犬,它们都接受了对侧肢体的各种外科手术,结果显示,只有一只犬在接受THR后结果良好,没有出现并发症[11]。在最近的一项研究中,所有13只犬在接受THR后3个月的随访中都获得了令人满意的结果[12]。

股骨头和股骨颈切除术或截骨术(FHO)是与本病例猫主人讨论过的治疗猫骨关节炎疼痛的另一种手术方案。最近一项调查猫FHO术后1年功能的研究报告称,尽管发现了猫的残余肢体步态异常,但骨科检查并未发现明显异常[13]。

之前一项对81只猫狗进行的研究显示,在FHO术后平均4年中,只有38%的病例肢体功能良好,20%的病例功能满意,42%的病例功能不满意[14]。一项仅涉及3只猫的小型研究报告称,与接受FHO的猫相比,接受THR的猫的功能结果更好[15]。根据这些文献中的结果,认为FHO并不是本病例中的三腿猫的最佳选择。

在本文报告的这只猫身上,一个有趣的现象是截肢肢体的髋关节骨关节炎的程度以及与该关节相关的疼痛。髋关节发育不良导致的髋关节骨关节炎在猫中已得到广泛认可,有报告称,60%-95.6%的猫在髋关节X光片上被确定为髋关节发育不良[23,24]。

目前还不清楚截肢髋关节中的骨关节炎是髋关节发育不良导致的退行性关节病的演变,还是由于关节生物力学的影响和截肢导致的活动受限。这确实提出了一个问题,即截肢后保留的关节即使不负重,是否也会成为动物疼痛的来源。在本病例中,猫在右髋关节手术6个月后,又一次切除了疼痛的左髋关节。

本病例表明,对于患有髋关节退行性关节病和对侧肢体截肢的猫来说,THR是一种可行的选择。截肢后残留的关节可能会发展成骨关节炎,成为猫疼痛的根源。

文献来源:Bourbos A, Piana F, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Total hip replacement in a cat with contralateral pelvic limb amputation. JFMS Open Rep. 2024 Apr 24;10(1):20551169241232297.

参考文献

1. Hardie EM, Roe SC, Martin FR. Radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease in geriatric cats: 100 cases (1994–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 220: 628–632.

2. Fischer HR, Norton J, Kobluk CN, et al. Surgical reduction and stabilization for repair of femoral capital physeal fractures in cats: 13 cases (1998–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 224: 1478–1482.

3. Kawamata T, Niiyama M, Taniyama H. Open reduction and stabilization of coxofemoral joint luxation in dogs and cats, using a stainless steel rope inserted via a ventral approach to the hip joint. Aust Vet J 1996; 74: 460–464.

4. Charnley J. The long-term results of low-friction arthroplasty of the hip performed as a primary intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1972; 54: 61–76.

5. Bardet JF. Cemented total hip replacement: experience in France with the Porte prosthesis. In: Vezzoni A. (ed). ESVOT 2004 Pre-Congress – total hip replacement seminar, 2004, p 14.

6. Hach V, Delfs G. Initial experience with a newly developed cementless hip endoprosthesis. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009; 22: 153–158.

7. Kalis RH, Liska WD, Jankovits DA. Total hip replacement as a treatment option for capital physeal fractures in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2012; 41: 148–155.

8. Preston CA, Schulz KS, Vasseur PB. Total hip arthroplasty in nine canine hind limb amputees: a retrospective study. Vet Surg 1999; 28: 341–347.

9. Johnson KA. Piermattei’s atlas of surgical approaches to the bones and joints of the dog and cat. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2014, Plate 67, pp 329–335.

10. Cook JL, Evans R, Conzemius MG, et al. Proposed definitions and criteria for reporting time frame, outcome, and complications for clinical orthopedic studies in veterinary medicine. Vet Surg 2010; 39: 905–908.

11. Contreras ET, Worley DR, Palmer RH, et al. Postamputation orthopedic surgery in canine amputees: owner satisfaction and outcome. Top Companion Anim Med 2018; 33: 89–96.

12. Gifford AB, Lotsikas PJ, Liska WD, et al. Total hip replacement in dogs with contralateral pelvic limb amputation: a retrospective evaluation of 13 cases. Vet Surg 2020; 49: 1487–1496.

13. Schnabl-Feichter E, Schnabl S, Tichy A, et al. Measurement of ground reaction forces in cats 1 year after femoral head and neck ostectomy. J Feline Med Surg 2021; 23: 302–309.

14. Off W, Matis U. Excision arthroplasty of the hip joint in dogs and cats. Clinical, radiographic and gait analysis findings at the surgical veterinary clinic of the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. Tierarztl Prax 1997; 25: 379–387.

15. Liska WD, Doyle N, Marcellin-Little DJ, et al. Total hip replacement in three cats: surgical technique, short-term outcome and comparison to femoral head ostectomy. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009; 22: 505–510.

16. Kulkarni J, Adams J, Thomas E, et al. Association between amputation, arthritis and osteopenia in British male war veterans with major lower limb amputations. Clin Rehabil 1998; 12: 274–279.

17. Struyf PA, van Heugten CM, Hitters MW, et al. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the intact hip and knee among traumatic leg amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 440–446.

18. Norvell DC, Czerniecki JM, Reiber GE, et al. The prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis among veteran traumatic amputees and nonamputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 487–493.

19. Hogy SM, Worley DR, Jarvis SL, et al. Kinematic and kinetic analysis of dogs during trotting after amputation of a pelvic limb. Am J Vet Res 2013; 74: 1164–1171.

20. Kirpensteijn J, Van Den Bos R, Van Den Brom WE, et al. Ground reaction force analysis of large breed dogs when walking after the amputation of a limb. Vet Rec 2000; 146: 155–159.

21. Fuchs A, Goldner B, Nolte I, et al. Ground reaction force adaptations to tripedal locomotion in dogs. Vet J 2014; 201: 307–315.

22. Amanatullah DF, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. Total hip arthroplasty after lower extremity amputation. Orthopedics 2015; 38: 394–400.

23. Langenbach A, Green P, Giger U, et al. Relationship between degenerative joint disease and hip joint laxity by use of distraction index and Norberg angle measurement in a group of cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 1439–1443.

24. Keller GG, Reed AL, Lattimer JC, et al. Hip dysplasia: a feline population study. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1999; 40: 460–464.

25. Paul HA, Bargar WL. A modified technique for canine total hip replacement. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1987; 23: 13–18.

26. Olmstead ML, Hohn RB, Turner TM. A five-year study of 221 total hip replacements in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983; 183: 191–194.

27. Massat BJ, Vasseur PB. Clinical and radiographic results of total hip arthroplasty in dogs: 96 cases (1986-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1994; 205: 448–454.

28. Dyce J, Wisner ER, Wang Q, et al. Evaluation of risk factors for luxation after total hip replacement in dogs. Vet Surg 2000; 6: 524–532.