| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:混种猫 |

| 年龄:8岁 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:是 | |

| 诊断:胃肠道间质瘤 | |

01 主诉及病史

两年来反复出现呕吐和厌食。

02 检查

体况评分4/9,体格检查时发现腹部中段可触及肿块,但无不适。其他临床指标(心率、呼吸频率、直肠温度、脉搏和粘膜)均无异常。

全血细胞计数显示白细胞增多(27300个/mm³ [5500-19000]),中性粒细胞增多(21840个/mm³ [3000-13000]),嗜酸性粒细胞增多(1911个/mm³ [60-850])。生化指标显示低白蛋白血症(2.0 g/dl [2.1-3.3])。猫白血病病毒(FeLV)抗原阴性,猫免疫缺陷病毒(FIV)抗体阴性。

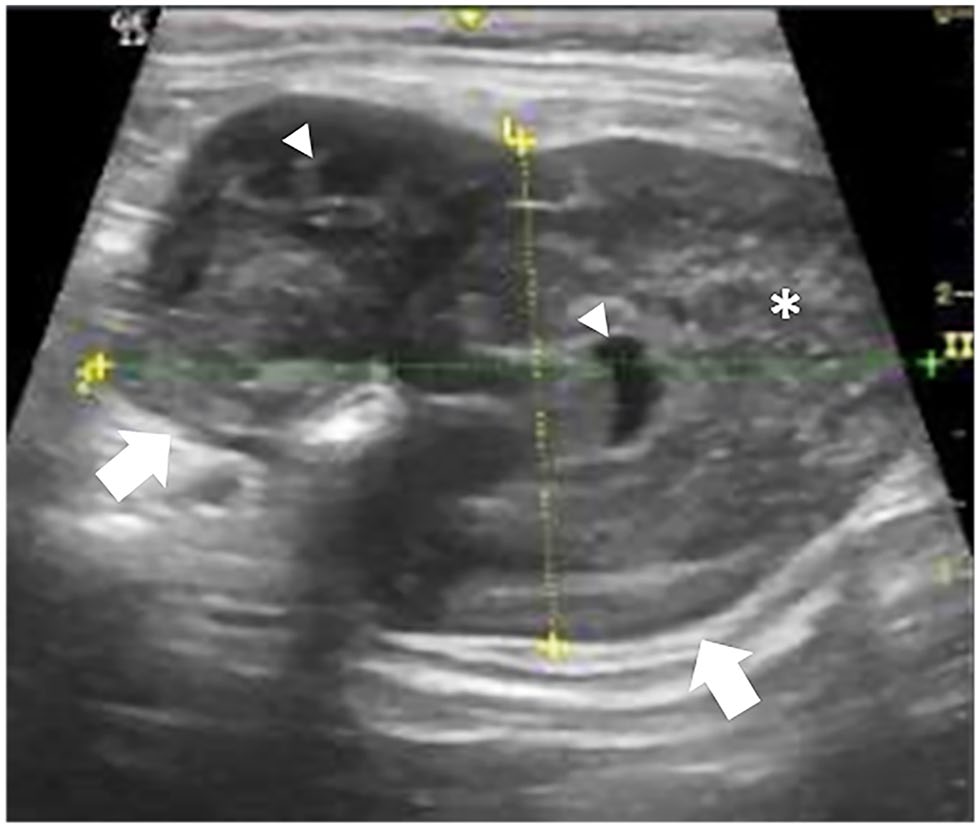

腹部超声显示,小肠(十二指肠)内有一个约5.19×3.57 cm肿块(下图),脾脏轻度肿大,肝脏形态均匀。

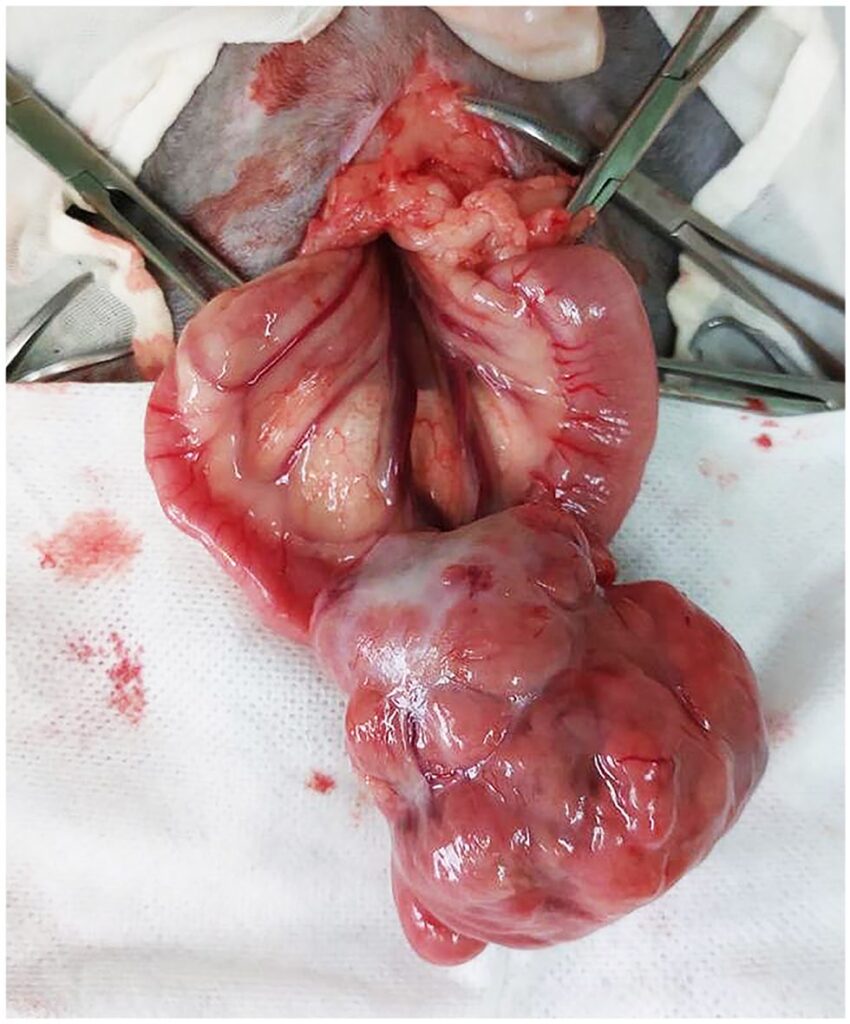

03 手术

患者接受了肠切除术,在十二指肠部位进行了3 cm切缘和端对端吻合术(下图)。未发现肿大的淋巴结、脾脏或肝结节。

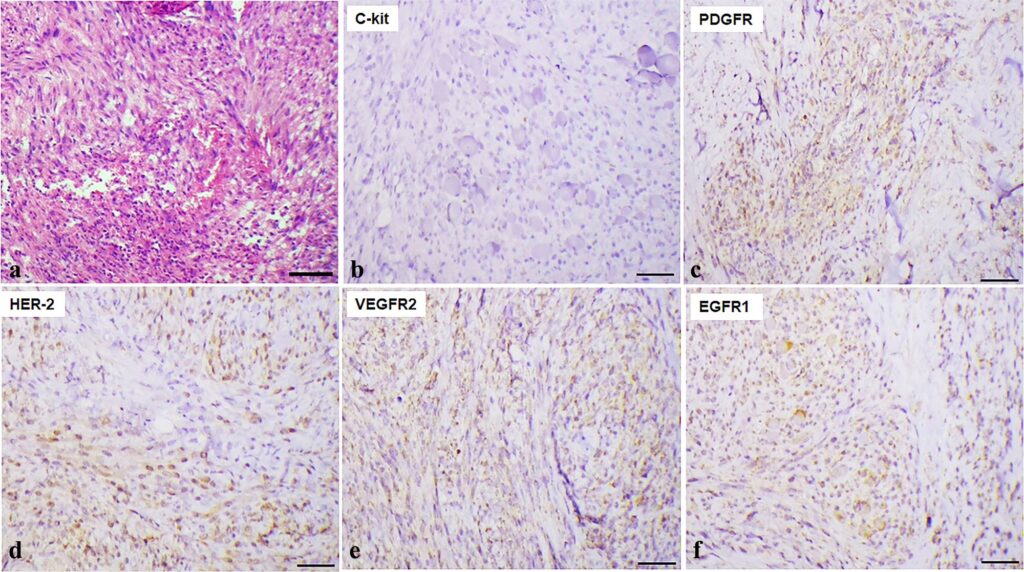

组织学检查结果显示,肌层内有肿瘤性细长细胞增生。肿块呈结节状、扩张性和浸润性。边界不清,无明显纤维包裹。有丝分裂指数为每高倍视野(400×)2/10(下图a)。初步诊断为低级别肉瘤(胃肠道间质瘤、平滑肌肉瘤或纤维肉瘤)。

对KIT蛋白、S100、1A4、Desmin和HHF35的免疫组化显示,只有KIT呈阳性,这证实了胃肠道间质瘤的诊断。约15%的肿瘤细胞的增殖指数(Ki67)呈阳性。HER-2(65%)和EGFR-1(50%)过度表达,VEGFR-2(35%)和PDGFR-beta(15%)表达减少,这表明可能存在靶向药物(下图b-f)。

根据组织学和免疫组化分析结果,建议进行辅助治疗,但由于个人原因,主人拒绝。因此,每3个月复查一次影像学检查。

04 预后

手术24小时后带药出院。药物包括:头孢氨苄(25 mg/kg PO q12h,持续7天)、美洛昔康(0.1 mg/kg PO q24h,持续5天)、氯酸曲马多(2 mg/kg PO q12h,持续5天)、双黄连(25 mg/kg PO q24h,持续5天)。术后10天的随访检查显示身体状况良好。没有呕吐和厌食情况。

3个月后第一次随访显示临床状况良好,超声检查没有发现转移病灶。

150天后,主人报告说患者开始呕吐,并伴有食欲不振。腹部触诊时有轻微腹部不适。超声检查发现肝脏、肠系膜和脾脏弥漫性结节性病变,提示有转移。腹部CT显示脾脏和肝脏有多灶性结节聚集,左腹部结肠外侧有结节区,其中夹杂着腹膜脂肪。肝区、胃区和胰十二指肠区均可见多灶性淋巴结病变(下图)。主人拒绝对肿块进行针刺活检或抽吸以确认这些病变是否是转移性的。

CT结果支持原发肿瘤进展,但在没有进一步诊断的情况下,无法排除炎症或其他肿瘤的可能性。不过考虑到患者的进展时间和随访情况,原发肿瘤进展的可能性要大于炎症或其他肿瘤发展的可能性。

根据肿瘤中KIT蛋白和HER-2的表达,考虑了两种可能的靶向药物:磷酸托塞瑞尼和拉帕替尼,它们都是酪氨酸激酶抑制剂。由于没有拉帕替尼在猫体内的治疗剂量,建议使用磷酸托塞瑞尼(帕拉丁),剂量为2.75毫克,每周用药3天,由于经济原因,40天后才开始用药。

通过腹部超声检查,在用药8周评估时观察到疾病进展,其中肝脏结节增大(2.0 cm增大至2.70 cm)。停用了帕拉丁(共使用了70天),并接受了姑息治疗。在撰写本报告时,患者仍然存活,但有持续性低氧血症。存活时间为485天(自最初诊断以来)。

05 讨论

胃肠道间质瘤(GIST)起源于Cajal间质细胞,该细胞调节胃肠道收缩[1-3]。将GIST与其他胃肠道肉瘤区分开来具有挑战性,因为影像学检查、形态学分析和HE染色不足以做出确诊[4-6]。

大多数GIST可根据KIT蛋白(CD117)的免疫反应进行鉴别[7]。在人类中,约有80-95%的GIST表达KIT蛋白[1]。然而,氯通道DOG-1被认为是犬GIST诊断的决定性因素,与KIT表达无关[1,5]。

KIT是一种酪氨酸激酶受体,在包括Cajal细胞在内的各种细胞类型的分化、增殖和迁移过程中发挥作用[4]。考虑到KIT阳性的GIST可采用磷酸托塞瑞尼治疗,因此区分平滑肌肉瘤和GIST的重要性在于治疗方法的选择[1]。

增殖生物标志物是兽医肿瘤学用于评估肿瘤细胞行为和疾病预后的重要工具[8]。最近,人类表皮生长因子受体2型(HER-2)在猫乳腺肿瘤中的表达被证明是一个潜在的治疗靶点,因为它在细胞生长中发挥作用,并与肿瘤细胞增殖有关[8]。

兽医文献中有关猫GIST的信息很少[9,10]。有两篇报道描述了猫胃和空肠GIST的不同生物学行为[9,10]。本病例报道是第一份关于猫转移性GIST长期存活的报告。

GIST可发生在胃肠道的任何部位,在人、狗、马、山羊、雪貂、大鼠和非人灵长类动物中均可观察到[14]。大肠是最常见的发病部位,其次是胃和小肠[15]。在本病例中,GIST位于小肠(十二指肠),与文献[11]中的病例报告相似。

GIST动物的临床症状因肿瘤位置、大小和分期而异。临床症状可能模糊不清,如体重减轻、呕吐、腹泻或便秘、腹痛和厌食[1]。本患者表现为呕吐、厌食和腹部不适。在这一阶段,仅出现低白蛋白血症(2.0 g/dl),这表明白蛋白流失、厌食导致代谢物输送减少、肝脏分泌减少或急性期炎症反应消极,促炎细胞因子释放导致反应减弱。

人和狗GIST的主要转移部位是肝脏和腹膜,肺转移并不常见[14,16]。在文献中,有两例已发表的猫GIST转移到肝脏的病例[9,10],本报告也观察到了这种情况。然而,除了肝转移外,本病例还观察到脾脏和腹膜转移,因为CT扫描上观察到了改变。

大约35%的人类GIST患者存活时间超过5年。如果出现远处转移,平均存活时间会缩短至19个月[17]。在狗中,手术切除后的存活时间为12个月[3]。

在狗和猫的GIST中,最常见的突变位于KIT的第11号外显子[4,12,21]。酪氨酸激酶抑制剂可抑制c-KIT信号转导,已成为不可切除肿瘤的一种治疗方式。VEGFR和PDGFR1[22]可为患者带来临床益处。最近一份关于一只GIST猫的报告显示,服用酸激酶抑制剂后病情稳定(30天)。

此外,该报告还显示KIT和PDGFRA基因的所有外显子均未发生突变,且免疫组化对KIT进行了细胞质染色[23]。在本报告中,也观察到KIT胞浆表达,但患者表现为疾病进展。另一份报告也显示KIT蛋白呈弱弥漫颗粒状胞浆反应,但服用酸激酶抑制剂后存活时间较长(18个月)。

除了这三个基因的表达外,本病例还有HER-2基因显著过表达,该基因在细胞周期的调节和分化中发挥重要作用[24]。拉帕替尼是EGFR1和HER-2的双重抑制剂,目前用于治疗狗的尿道癌[24]。

最近,一项体外研究显示,使用拉帕替尼治疗猫乳腺癌的效果很好[25]。鉴于HER-2和EGFR1的过度表达,进一步研究将拉帕替尼作为猫的一种治疗选择,将为进一步了解这种罕见的转移性疾病提供机会。

总之,GIST在猫中非常罕见,由于缺乏相关文献,人们对其临床表现仍然知之甚少。使用基于HER-2过表达的酪氨酸激酶抑制剂可能是控制猫转移性GIST的一种有效策略。

文献来源:Civa PAS, Fonseca-Alves CE, Dos Anjos DS. Long-term survival of a cat with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Open Reports. 2024;10(1).

参考文献

1. Berger EP, Johannes CM, Jergens AE, et al. Retrospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate (Palladia) use in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2018; 32: 2045–2053.

2. Katz SC, Ronald PD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcomas. J Surg Oncol 2008; 97: 350–359.

3. Streuker CJ, Huizinga JD, Driman DK, et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal in health and disease, part II: ICC and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Histopathology 2007; 50: 190–202.

4. Morini M, Gentilini F, Pietra M, et al. Cytological, immunohistochemical and mutational analysis of a gastric gastrointestinal stromal cell tumour in a cat. J Comp Pathol 2011; 145: 152–157.

5. Dailey DD, Ehrhart EJ, Duval DL, et al. DOG1 is a sensitive and specific immunohistochemical marker for diagnosis of canine gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Vet Diagn Invest 2015; 27: 268–277.

6. Fernandez R, Chon E. Comparison of two melphalan protocols and evaluation of outcome and prognostic factors in multiple myeloma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2018; 32: 1060–1069.

7. Debiec-Rychter M, Wasag B, Stul M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) negative for KIT (CD117 antigen) immunoreactivity. J Pathol 2004; 202: 430–438.

8. Gameiro A, Urbano AC, Ferreira F. Emerging biomarkers and targeted therapies in feline mammary carcinoma. Vet Sci 2021; 8.

9. McGregor O, Moore A, Yeomans S. Management of a feline gastric stromal cell tumour with toceranib phosphate: a case study. Aust Vet J 2020; 98: 181–184.

10. Suwa A, Shimoda T. Intestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a cat. J Vet Med Sci 2017; 79: 562–566.

11. Blackwood L, Harper A. Toxicity and response in cats with neoplasia treated with toceranib phosphate. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 619–623.

12. Berger EP, Johannes CM, Post GS, et al. Retrospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate (Palladia) use in cats with mast cell neoplasia. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 95–102.

13. Eisenhauer E, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 228–247.

14. Frost D, Lasota J, Miettinen M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyomas in the dog: a histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 50 cases. Vet Pathol 2003; 40: 42–54.

15. Gillespie V, Baer K, Farrelly J, et al. Canine gastrointestinal stromal tumors: immunohistochemical expression of CD34 and examination of prognostic indicators including proliferation makers Ki67 and AgNOR. Vet Pathol 2011; 48: 283–291.

16. Suresh Babu MC, Chaudhuri T, Govind Babu K, et al. Metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a regional cancer center experience of 44 cases. South Asian J Cancer 2017; 6: 118–121.

17. DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, et al. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Surg 2000; 231: 51.

18. Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol 2008; 39: 1411–1419.

19. Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era-a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer 2005; 103: 821–829.

20. Li J, Wang AR, Chen XD, et al. Ki67 for evaluating the prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Lett 2022; 23: 189.

21. Gregory-Bryson E, Bartlett E, Kiupel M, et al. Canine and human gastrointestinal stromal tumors display similar mutations in c-KIT exon 11. BMC Cancer 2010; 10.

22. London CA, Hannah AL, Zadovoskaya R, et al. Phase I dose-escalating study of SU11654, a small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in dogs with spontaneous malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 2755–2768.

23. Fujii Y, Iwasaki R, Ikeda S, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour lacking mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 2022; 63: 239–243.

24. Maeda S, Sakai K, Kaji K, et al. Lapatinib as first-line treatment for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma in dogs. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 4.

25. Gameiro A, Almeida F, Nascimento C, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are promising therapeutic tools for cats with HER2-positive mammary carcinoma. Pharmaceutics 2021; 13.