| 一般情况 | |

|---|---|

| 品种:短毛猫 |

| 年龄:15岁 | |

| 性别:雌 | |

| 是否绝育:是 | |

| 诊断:脑膜瘤 | |

01 主诉及病史

进行性瘫痪、强迫性步态,双侧威胁消失和向右绕圈。

02 检查

血液学、生化、电解质、总甲状腺素和果糖胺均在参考范围内。心率为140次/分,外周脉搏同步。ASA(美国麻醉学会)评分为3分。

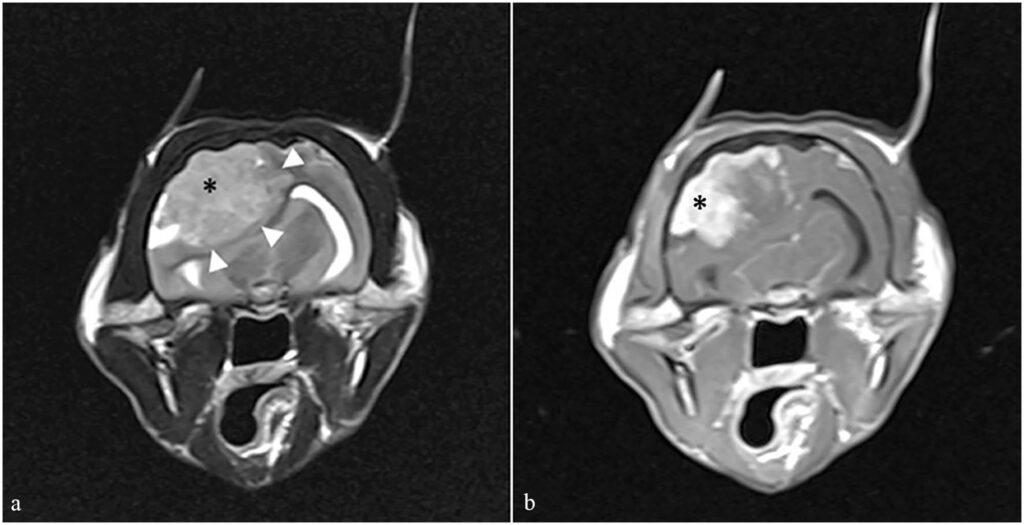

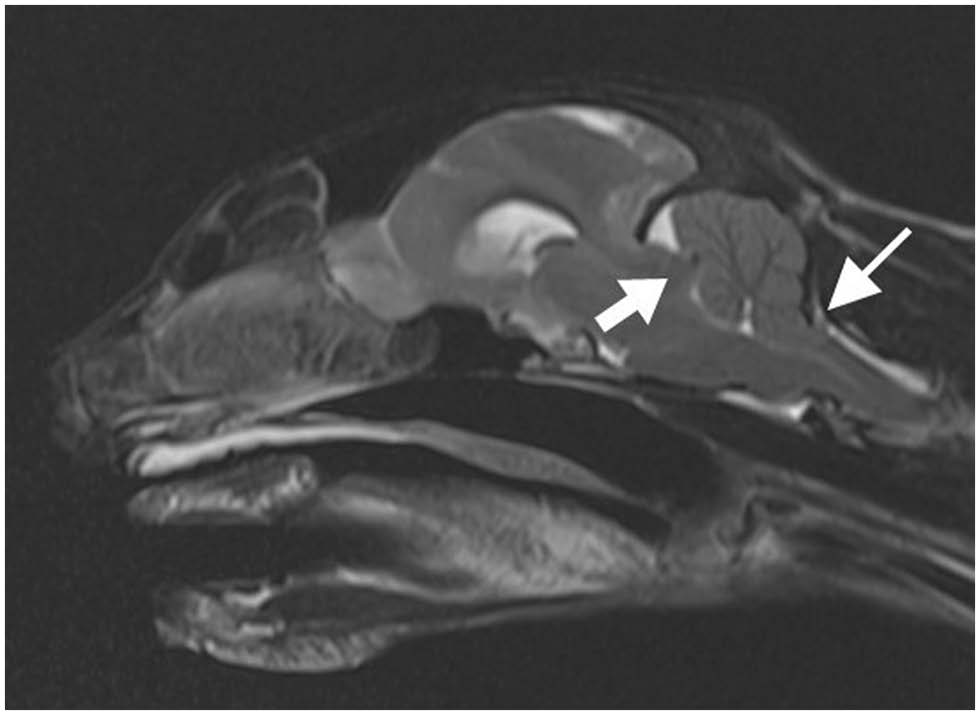

核磁共振成像显示脑膜瘤导致中线移位、尾部横隔和枕骨大孔疝(下图)。为了降低颅内压,30分钟内静脉注射了地塞米松0.2 mg/kg和甘露醇0.5 g/kg。核磁共振成像期间,脉搏为68次/分,平均动脉压为59 mmHg(45-67)。

在地塞米松和甘露醇注射15分钟后,静脉注射7%高渗盐水2 mL/kg,持续10分钟。为避免增加脑血流量,未对心动过缓进行处理,并将潮气末七氟醚维持在<1.6%,以减少血管扩张。在使用高渗盐水治疗后,动脉血压有所改善。

03 手术

核磁共振检查后,紧急进行了右侧喙突开颅手术。术中添加了医用空气,使吸入氧分压达到0.6,并维持IPPV,EtCO2为32(26-46)mmHg。在开始颅骨钻孔前,注射了2 mL/kg的高渗盐水。手术期间,心率为每分钟79(69-93)次,血压为62(52-115)mmHg。

术中进行了连续动脉血气分析,显示存在代谢性酸中毒和呼吸性酸中毒。通过调整呼吸机设置,后者得到了改善。通过使用PaCO2和EtCO2计算修订后的玻尔方程,推测目前存在的通气/灌注不匹配很可能是由于死腔通气造成的。血细胞比容在手术前后一直很低,这可能是由于麻醉期间红细胞在血液循环外被螯合造成的。由于α-2-肾上腺素受体激动剂以及手术操作的影响,整个麻醉过程中都存在高血糖。

手术进行得很顺利,肿块被完全切除。肿块的组织病理学分析诊断为上皮样脑膜瘤。

04 预后

停止机械通气后立即进行自主通气。右美托咪定的恒速输注每30分钟减半,以避免患者在恢复过程中出现兴奋。拔管两小时后,心率(108次/分)和血压(80 mmHg)均有所改善。

术后住院期间,心率为每分钟80(120-210)次,收缩压为127(112-220)mmHg。术后接受了地塞米松0.2 mg/kg静脉注射,q24h、头孢呋辛20 mg/kg静脉注射,q8h、丁丙诺啡0.02 mg/kg静脉注射,q8h。

术后3天出院。术后3周开始逐渐减少泼尼松龙的抗炎剂量并停药。

术后8周,神经系统检查正常,只是左侧威胁反应略有减弱。

术后8个月,主人报告说猫的行为恢复正常,没有明显的神经功能障碍。

05 讨论

虽然猫科动物颅内肿瘤可能会导致脑疝,但不会出现特定的神经症状[4,5],但在本病例中,昏迷和神志不清的症状提示可能存在颅内压增高。因此,全面的麻醉前评估对于制定适当的麻醉计划非常重要[6]。

颅腔由三部分组成:脑实质、脑脊液和血液(动脉和静脉)。根据Monro-Kellie理论[7],由于颅骨的固定性,它们的体积总和应保持恒定,以维持5-12 mmHg的生理性颅内压[8]。颅内压的增加是颅内任一内容物体积增加的结果,从而导致脑灌注压和脑脊液的改变。

在数学上,脑灌注压=平均动脉压-颅内压。因此,要保持大脑充分灌注,平均动脉压必须高于颅内压。在颅内压增加的情况下,全身血管阻力的增加将提高平均动脉压并维持脑灌注压。因此,主动脉和颈动脉气压感受器受到刺激,导致反射性心动过缓。颅内压升高对脑干的压迫也会导致呼吸中枢受压,造成不规则的呼吸模式,这就是库欣反射(Cushing’s reflex,CR)[9]。

CR是一种公认的与颅内压相关的心血管反射,但在人类医学中,据报道它对检测颅内压升高的灵敏度较低[10]。虽然在犬中,入院时较高的血压和较低的心率与脑疝的存在有关[11],但在猫中却没有发现这种情况[12]。一项针对接受颅内脑膜瘤手术切除猫的回顾性研究报告称,在一些通过持续监测确认颅内压升高的患者中没有出现CR[4]。

在本病例中,核磁共振成像和手术期间均持续记录到心动过缓和轻度低血压。在手术过程中,血压和心率在手术前后均保持稳定。在开颅手术过程中,即使没有高血压,心动过缓和心搏骤停也经常发生在人类身上。此外,术中动脉低血压也经常出现[13-15]。

有研究认为,颅内压增高的患者心动过缓可能是由于位于延髓的迷走神经核受到直接压迫所致[16,17]。核磁共振成像显示尾部横隔疝、中线移位和枕骨大孔疝,这可能会对脑干造成高压[18]。

虽然低血压会导致脑灌注和氧输送减少,但在本病例中,低血压可能与心动过缓有关。医生决定不对其进行治疗,因为增加心率可能会导致脑脊液增加,从而升高颅内压。手术期间,患者一直处于低体温状态(食道温度 32.7-34.2°C)。低体温可能会导致心动过缓和低血压[19]。

麻醉师选择治疗性低温来降低颅内压[20],尽管这种治疗方法在人类医学中的风险效益评估仍无定论。一些研究表明,直肠温度低于35°C时氧的输送和消耗会减少[21],但在颅骨减压切除术后保持33-34°C的温度可降低严重脑肿胀患者的颅内压[20]。Sakoh和Gjedde[22]提出,将体温降至32°C可能会通过恢复脑代谢和脑灌注之间的生理平衡而起到保护神经的作用。

α-2-肾上腺素受体激动剂用药后常见心动过缓,但这种心血管效应与剂量有关[23]。在术前用药和手术中使用的低剂量预计会对心率和全身血管阻力产生轻微影响。作者认为心血管变化可能与颅内压增高有关,因此治疗的目的是降低颅内压。

临床上经常使用甘露醇和高渗盐水降低患者的颅内压。甘露醇具有扩容和渗透性利尿作用。它能使液体从细胞间隙和细胞内空间转移到血管内,并降低血液粘度。它还能增加大脑的供氧量,导致脑血管收缩和脑脊液增加。

高渗盐水通过其渗透作用以类似的方式发挥作用。在这种情况下,使用高渗盐水还因为其有利的血液动力学特性,如增加心输出量和血压[33]。高渗盐水还可通过降低白细胞粘附性起到抗炎作用[34]。在人类医学中,有人认为高渗盐水在降低颅内压方面可能优于甘露醇[35],但其他报告则认为两者没有区别。在MRI期间,猫接受了地塞米松治疗。据报道,皮质类固醇有利于减轻瘤周血管性水肿[36]。

在麻醉期间,虽然CR通常与颅内压的突然增加有关,但也需要将其他血流动力学变化视为警告信号,如无高血压的心动过缓,尤其是在麻醉前已出现脑疝的患者中。

参考文献

[1] American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. www.asahq.org/standards-and-practice-parameters/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system (2020, accessed 9 August 2023).

[2] Dhumeaux MP, Snead EC, Epp TY, et al. Effects of a standardized anesthetic protocol on hematologic variables in healthy cats. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 701–705.

[3] Fagerholm V, Haaparanta M, Scheinin M. α2-Adrenoceptor regulation of blood glucose homeostasis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2011; 108: 365–370.

[4] Kouno S, Shimada M, Sato A, et al. Surgical treatment of rostrotentorial meningioma complicated by foraminal herniation in the cat. J Feline Med Surg 2020; 22: 1230–1237.

[5] Troxel MT, Vite CH, Winkle TJV, et al. Feline intracranial neoplasia: retrospective review of 160 cases (1985–2001). J Vet Intern Med 2003; 17: 850–859.

[6] Louro LF, Maddox T, Robson K, et al. Pre-anaesthetic clinical examination influences anaesthetic protocol in dogs undergoing general anaesthesia and sedation. J Small Anim Pract 2021; 62: 737–743.

[7] Monro A. Observations on the structure and functions of the nervous system. Lond Med J 1783; 4: 113–135.

[8] Dewey CW. Head trauma management. In: Dewey CW, da Costa RC. (eds). A practical guide to canine and feline neurology. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, 2016, pp 237–248.

[9] Cushing H. Concerning a definite regulatory mechanism of the vasomotor centers which controls blood pressure during cerebral compression. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1901; 12: 290.

[10] Ter Avest E, Taylor S, Wilson M, et al. Prehospital clinical signs are a poor predictor of raised intracranial pressure following traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med J 2021; 38: 21–26.

[11] Her J, Yanke AB, Gerken K, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the relationship between admission variables and brain herniation in dogs (2010–2019): 54 cases. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2022; 32: 50–57.

[12] Her J, Merbl Y, Gerken K, et al. Relationship between admission vitals and brain herniation in 32 cats: a retrospective study. J Feline Med Surg 2022; 24: 770–778.

[13] Bilotta F, Guerra C, Rosa G. Update on anesthesia for craniotomy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2013; 26: 517–522.

[14] Haldar R, Prakhar G, Guruprasad B. Isolated bradycardia due to skull pin fixation: an unusual occurrence. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2013; 25: 206–207.

[15] Vimala S, Arulvelan A. Sudden bradycardia and hypotension in neurosurgery: trigeminocardiac reflex (TCR) and more. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2016; 28: 175–176.

[16] Tsai Y-H, Lin J-Y, Huang Y-Y, et al. Cushing response-based warning system for intensive care of brain-injured patients. Clin Neurophysiol 2018; 129: 2602–2612.

[17] Cho S-M, Kilic A, Dodd-o JM. Incomplete Cushing’s reflex in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Int J Artif Organs 2020; 43: 401–404.

[18] Walmsley GL, Herrtage ME, Dennis R, et al. The relationship between clinical signs and brain herniation associated with rostrotentorial mass lesions in the dog. Vet J 2006; 172: 258–264.

[19] Dahlen RW. Some effects of hypothermia on the cardiovascular system and ECG of cats. Exp Biol Med 1964; 115: 1–4.

[20] Rim HT, Ahn JH, Kim JH, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia for increased intracranial pressure after decompressive craniectomy: a single center experience. Korean J Neurotrauma 2016; 12. DOI: 10.13004/kjnt.2016.12.2.55.

[21] Tokutomi T, Morimoto K, Miyagi T, et al. Optimal temperature for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: effect of hypothermia on intracranial pressure, systemic and intracranial hemodynamics, and metabolism. Neurosurgery 2003; 52: 102–112.

[22] Sakoh M, Gjedde A. Neuroprotection in hypothermia linked to redistribution of oxygen in brain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003; 285: H17–H25.

[23] Pypendop BH, Verstegen JP. Hemodynamic effects of medetomidine in the dog: a dose titration study. Vet Surgery 1998; 27: 612–622.

[24] Murrell JC. Pre-anaesthetic medication and sedation. In: Duke-Novakovski T, de Vries M, Seymour C. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline anaesthesia and analgesia. Quedgeley: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2016, pp 170–189.

[25] Lin N, Vutskits L, Bebawy JF, et al. Perspectives on dexmedetomidine use for neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2019; 31: 366–377.

[26] Wang L, Shen J, Ge L, et al. Dexmedetomidine for craniotomy under general anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Anesth 2019; 54: 114–125.

[27] Soliman RN, Hassan AR, Rashwan AM, et al. Prospective, randomized study to assess the role of dexmedetomidine in patients with supratentorial tumors undergoing craniotomy under general anaesthesia. Middle East J Anesthesiol 2011; 21: 325–334.

[28] Engelhard K, Werner C. Inhalational or intravenous anesthetics for craniotomies? Pro inhalational. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006; 19: 504–508.

[29] Andress JL, Day TK, Day DG. The effects of consecutive day propofol anesthesia on feline red blood cells. Vet Surgery 1995; 24: 277–282.

[30] Pascoe PJ, Ilkiw JE, Frischmeyer KJ. The effect of the duration of propofol administration on recovery from anesthesia in cats. Vet Anaesth Analg 2006; 33: 2–7.

[31] Tameem A, Krovvidi H. Cerebral physiology. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2013; 13: 113–118.

[32] Leece EA. Neurological disease. In: Duke-Novakovski T, de Vries M, Seymour C. (eds). BSAVA manual of canine and feline anaesthesia and analgesia. Quedgeley: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2016, pp 392–409.

[33] Bitterman H, Triolo J, Lefer A. Use of hypertonic saline in the treatment of hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock 1987; 21: 271–283.

[34] Torre-Healy A, Marko NF, Weil RJ. Hyperosmolar therapy for intracranial hypertension. Neurocrit Care 2012; 17: 117–130.

[35] Kamel H, Navi BB, Nakagawa K, et al. Hypertonic saline versus mannitol for the treatment of elevated intracranial pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit Care Med 2011; 39: 554–559.

[36] Bebawy JF. Perioperative steroids for peritumoral intracranial edema: a review of mechanisms, efficacy, and side effects. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2012; 24: 173–177.